KAMPALA, Uganda—This country has long been a haven for Africans fleeing war and famine. No longer.

Uganda is among a raft of poorer countries pulling back the welcome mat, which officials here blame on deep cuts to American aid. The move is the latest sign that impoverished nations are joining far wealthier states in turning desperate people away.

“We have now decided to narrow the support to only vulnerable refugees,” Geoffrey Mugabe , a senior official in the Ugandan prime minister’s office, said. “Registration of refugees from countries that are not in conflict has been closed.”

The new restrictions, announced in October, have prevented the entry of 5,000 refugees into the country, according to government estimates.

Even people fleeing Somalia, a country mired in civil war and Islamist violence for decades, are being turned away at Ugandan border crossings, according to Mugabe.

Egypt, Kenya and Ethiopia are also moving to restrict new refugees, citing funding shortages, aid agencies say. People escaping the civil war in Sudan now need visas to enter Egypt, or run the risk of deportation. Ethiopia has also revoked visa exemptions and police routinely detain people lacking the necessary paperwork, aid officials say.

Kenya’s courts are considering government plans to stop registering asylum seekers from Eritrea and Ethiopia, while Chad’s government warned in June that it may be forced to close its land border with Sudan because of insufficient international support for the nearly one million people who have crossed into its territory.

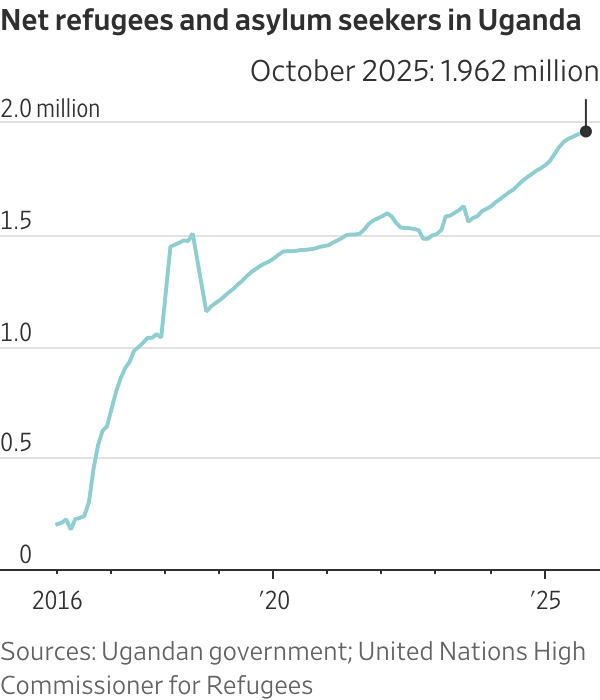

Uganda had been a notable exception to a worldwide pull-up-the-drawbridge trend, granting shelter to almost two million desperate neighbors, allowing them to work and even giving many of them land to farm. In 2021, it became the first African country to accept Afghan refugees evacuated after the Taliban ousted the Kabul government. Under a deal with Washington in August, Uganda agreed to take in U.S. deportees who believe it unsafe to return to their countries of origin. Uganda has yet to receive any such deportees.

“I am trying to build my future from here,” said Alberdine Mohamed , who fled to Uganda from Sudan in 2023. His children attend Ugandan schools and his wife has started a business in Kampala, the capital.

Uganda is in a rough neighborhood, and there is no shortage of people fleeing conflict in nearby countries. There is war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and fresh clashes between political factions in South Sudan. Sudan itself has been engulfed in civil war for more than two years.

“Ultimately, our goal has always been to ease the suffering of migrants and refugees,” said Patrick Okrut , Uganda’s commissioner responsible for migration.

Refugees and asylum seekers constitute 3.9% of Uganda’s population, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council. (By comparison, the same figure in far wealthier Norway stands at 2.4%.) It has taken a $380 million World Bank loan to build schools, hospitals, and sanitary facilities in crowded camps and host communities.

The U.S. hosts 3.6 million refugees and asylum seekers, a large number but just 1.1% of its population. In Europe, Germany, long open to migrants, is now rejecting many of them under a new policy announced in May. Migrants who illegally enter Italy or France risk being detained in filthy, overcrowded camps, according to the United Nations refugee agency. The European Union pays African nations to block migrants from crossing the Mediterranean.

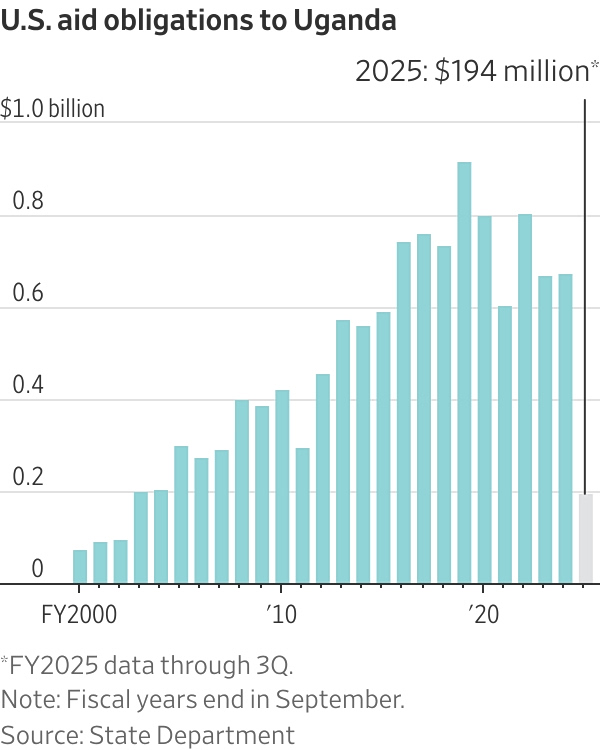

Uganda’s generosity, however, depended on U.S. generosity. In the final year of the Biden administration, the U.S. contributed $83 million in food, medical and education assistance that Uganda provided to refugees.

Soon after taking office in January, Trump effectively dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development, the traditional conduit for American foreign assistance.

Now Uganda says it can no longer afford to play host to Africa’s neediest, while political pressure to close the door is also growing, especially in the country’s north, where there is growing competition for land and resources between locals and refugees.

“They are not allowing any of my family members here,” said Anastazia Bununsi , an Eritrean waitress who came to Kampala as an asylum seeker. “If I get a better option, I will try to leave Uganda.”

Tommy Pigott , the State Department’s deputy spokesman, said the Trump administration, dismissed the idea that the obligation to provide aid falls solely on the U.S. “The Trump administration has continuously called on nations around the world to join the United States in offering humanitarian assistance to vulnerable populations,” he said. “The U.S. is the world’s most generous nation, but we’re not the only one that can help.”

The U.N. budget for refugee services in Uganda has fallen from $500 million in 2019 to around $140 million this year. As of August, the U.N. had received only 18% of its $968 million appeal to fund refugee and other aid programs in Uganda this year, according to U.N. data.

In one settlement near Uganda’s border with South Sudan, refugee families are eating just two or three meals a week, leaving nearly a third of the children in the camp malnourished, according to Food for the Hungry, a charity. In settlements close to the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo, health officials are turning away patients seeking treatment for bacterial infections in favor of more urgent cases, aid officials say. At another settlement, the U.N. refugee agency has run out of blankets, tarpaulins and sleeping mats, forcing refugees to sleep in the open.

In most refugee settlements, the government has run out of land to allocate to migrants for crop cultivation, and in at least one, refugees have come to blows over the plots that are available.

“The living conditions in settlements are extremely poor and deeply concerning,” said Godfrey Ayena , director of Food for the Hungry’s Uganda office, which runs a malnutrition-treatment program.

Humanitarian agencies are urging the Ugandan government to maintain its open-door policy. But government officials say budgets are so constrained that the only available option is to encourage some refugees to return home, despite the risks they would face.

Since the start of the year, more than 4,000 refugees have abandoned Ugandan encampments, opting to return to Burundi, South Sudan and other countries, according to the U.N. refugee agency.

By year’s end, some 2,000 refugees are expected to return to a precarious future in Sudan, considered by aid workers to be immersed in the world’s worst humanitarian crisis as its brutal civil war drags on.

Write to Nicholas Bariyo at nicholas.bariyo@wsj.com