LONDON— Keir Starmer entered Downing Street in 2024 with a large majority and a mandate to bring calm to British politics after years of crises and wild policy shifts.

Just 19 months later, Starmer is one of Britain’s least popular leaders in modern times and is hanging to power by a thread. Most analysts say it’s a question of when, not if, he departs. That would put Britain on course for its fifth new leader in seven years, an unsettling prospect for businesses and investors.

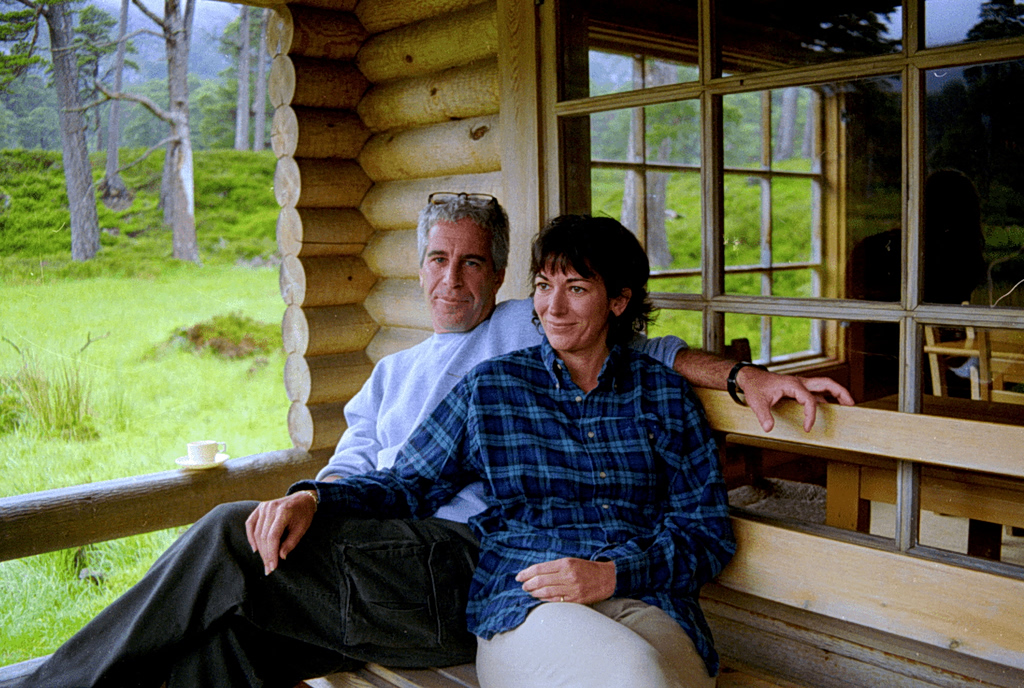

The immediate crisis is the Epstein files and revelations that Starmer’s pick to be British ambassador to Washington, Peter Mandelson , was far more deeply entwined with the convicted sex offender than previously known. Starmer has apologized for hiring the Labour Party grandee, and Mandelson has quit the House of Lords—the British Parliament’s upper chamber—amid a police investigation into whether he shared market-sensitive information with the financier. Mandelson hasn’t responded to requests for comment.

The scandal is now taking a life of its own, as disgruntled Labour lawmakers threaten to use it to drum out the unpopular Starmer. Over the weekend, the prime minister sacrificed his chief of staff , Morgan McSweeney, an old protégé of Mandelson’s who took the blame for advising Starmer to hire the former Labour minister.

On Monday, Downing Street’s head of communications quit, adding to the sense of turmoil. He was the fourth person to hold the job in the past year. Hours later, the head of the Scottish Labour Party, Anas Sarwar , called on Starmer to step down. “The distraction needs to end,” he said.

Starmer got a boost after a host of his cabinet members came out in support. A government spokesman denied that he was about to step down, saying he was “focusing on the job in hand.” On Monday, Starmer dug in, telling staff in Downing Street to “go with confidence as we continue changing the country” while listing successes such as cutting waiting lists for hospital appointments, an official present at the meeting told reporters. Starmer was due to meet with Labour lawmakers later on Monday.

Underpinning this revolt is a simple fact: Starmer’s popularity with the public has cratered and his lawmakers are getting increasingly worried about their job prospects, even though an election isn’t due until 2029. A recent Ipsos poll showed Starmer is liked by just 20% of Brits and disliked by 70%. Labour now sits in third place behind the populist anti-immigration Reform UK party and the Conservative Party, according to most polls.

“He can stagger on, but it’s hard to see how he lasts the year,” said Rob Ford , a political scientist at the University of Manchester.

The biggest saving factor for Starmer is there is no obvious front-runner to replace him and the process to oust him is long and complex. Former Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner is popular with Labour Party members, but is currently being investigated by tax authorities after admitting to underpaying tax on a property she purchased. Wes Streeting , the health secretary, has been touted as a rising star on the left, but also has ties to Mandelson.

No governing Labour leader has ever been dethroned while in office. “There is always a way through for the prime minister,” said James Lyons, who until recently served as Starmer’s director of communications. “But the path to survival has become much narrower and much steeper.”

The pressure is only likely to increase. There is a special election for an empty parliamentary seat in late February and local elections in May. Polls show that Reform is expected to do well in traditional Labour strongholds, likely fueling momentum to oust Starmer.

On top of this, lawmakers this week voted to publish all the correspondence between Mandelson and Downing Street over his appointment as ambassador, which could produce yet more embarrassing, headline-fueling details.

A Labour Party mutiny against Starmer would extend a long period of uncertainty that has dogged the U.K. for the past decade, including Britain’s drawn-out divorce from the European Union, the chaos of the pandemic and a revolving door of leaders, including the 49-day tenure of Conservative Liz Truss , who sparked a run on the pound by unveiling unfunded tax cuts. The uncertainty has hurt business investment and weakened the economy.

The most damaging revelations from the correspondence in the Epstein files so far appear to show that Mandelson, as a cabinet minister, sent emails to Epstein with market-sensitive information on government policy that could have allowed him to trade on the inside information. Mandelson hasn’t commented on those emails.

“This is a major scandal. People can argue about whether you should have kept up a relationship of any kind with someone who was in jail, but everyone agrees you do not provide privileged financial information as a government minister,” said John Curtice, a professor of politics at the University of Strathclyde. “Starmer has so little political capital, that this is like a perfect storm.”

Replacing Starmer would increase the pressure for an early general election, something many Labour lawmakers will be wary of given their standing in the polls. And there is an awareness among many in Labour that the noise and disruption is bad for Britain’s economy and standing, said Tony Travers, a political expert at the London School of Economics.

The 63-year-old Starmer is a relative newbie to British politics, only having entered the House of Commons in 2015. He isn’t known for rousing oratory or catchy sound bites; the former prosecutor instead prefers to talk in long, earnest sentences about fairness and duty.

Starmer’s bet was that dry pragmatism would bring breathing space, allowing investors confidence and giving voters a break from daily headlines about chaotic politics. Starmer’s political allies say a no-frills approach is showing signs of success, with interest rates falling and inflation trending down. Several U.K. indicators show that business confidence is up.

But his time in office has been marred by what critics say is indecision, bad luck and the fact that he seemed to enter Downing Street with no clear road map of how to pull Britain’s economy out of the doldrums. Within weeks of getting into office, he ditched his first chief of staff. After three months he tried to shore up his nosedive in the polls with a strategy titled “Plan for Change – Milestones for A Mission Led Government.”

On the international stage, Starmer managed to curry favor both with President Trump and European leaders, a major feat of diplomacy. His frequent trips abroad earned him the moniker in the British press of “Never Here Keir.”

His domestic agenda, meanwhile, has been filled with retreats: A promise not to increase taxes was junked; a pledge to chop welfare spending abandoned amid a revolt by his own party; a reshaping of the British state, with the issuing of digital ID cards, watered down. He has helped reduce record levels of legal immigration, but struggled to slow rising arrivals of asylum seekers crossing the English Channel in small boats—a phenomenon that has buoyed Reform UK.

Ford, the political scientist, compared Starmer’s situation to that of former Conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson in early 2022, when a string of scandals left him vulnerable. One further scandal that summer, involving an aide making unwanted advances to other men at a club, caused a series of resignations among Johnson’s cabinet members that proved his undoing.

“The Labour herd are restive; we just don’t know what the gunshot on the prairie might be to cause a stampede for the exits. At some point, the gunshot will arrive,” Ford said.