In the aftermath of the U.S. raid to seize Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro , Washington is trying a new approach to regime change: Keep the regime—and try to change its behavior.

Having removed Maduro from power, the Trump administration has kept the rest of the dictatorship’s hard-liners in place, including top officials wanted by the U.S. for drug trafficking and other crimes. It also has gone out of its way to play down the importance of the Venezuelan opposition.

The goal, administration officials say, is to force Venezuela’s leaders in a more U.S.-friendly direction without risking the instability that comes with removing an autocratic government that has been in power for 27 years. Ultimately, it seeks to avoid U.S. boots on the ground in the kind of open-ended occupation that troubled U.S. efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan and proved unpopular with the American public.

“This is not regime change as traditionally conceived. It is regime management—an attempt to reshape behavior without collapsing the system that produces it,” said Christopher Hernandez Roy, an analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., who specializes in Latin America.

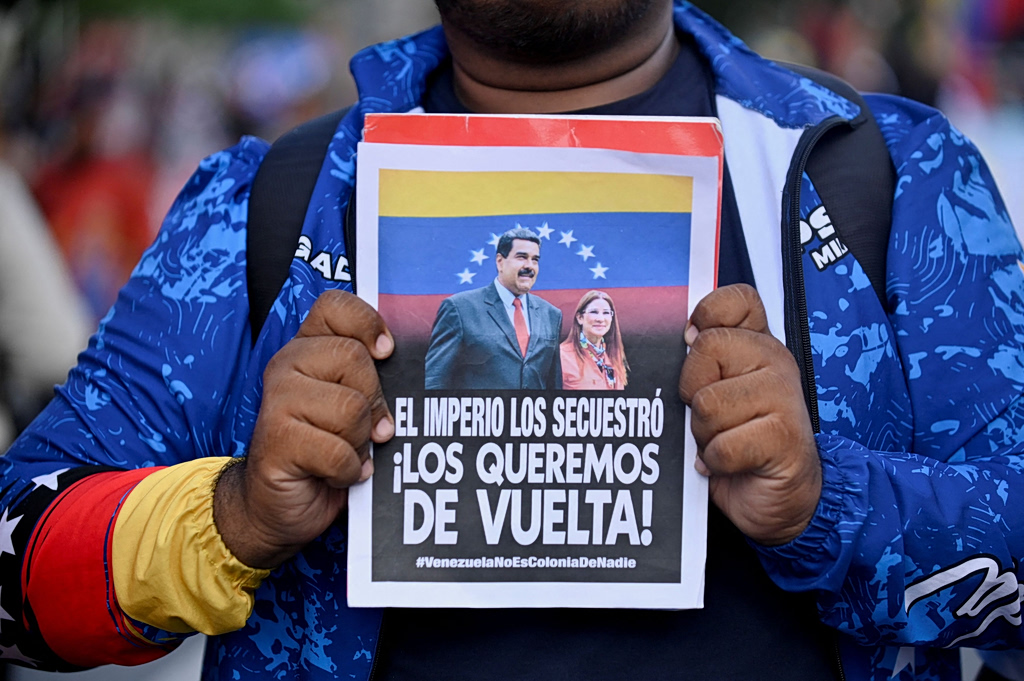

A supporter holds a sign reading “The empire took them. We want them back!” during a march calling for the release of Venezuela’s ousted President Nicolas Maduro, days after he and his wife, Cilia Flores, were captured by U.S. forces following U.S. strikes on Venezuela, in Caracas, Venezuela, January 8, 2026. REUTERS/Maxwell Briceno

The idea, he said, is to manage Venezuela rather than liberate it.

It is far too early to tell if the strategy will pay off. But its initial success means it could become a template for handling other regimes such as the one in Iran, where the Trump administration is considering strikes against the country’s theocratic government amid a crackdown on protests. Cuba’s ossified communist regime could be another target, analysts say.

By taking out Maduro, the Trump administration hopes to get practical change on the cheap, including forcing Venezuela to open its oil industry to U.S. and foreign companies, reduce the flow of drugs to the U.S., and box out China, Russia and Iran. Any kind of transition to democracy seems a lower priority, at least for now.

The approach might be called “nation-coaching” rather than nation-building, said Javier Corrales, a political scientist whose research at Amherst College has focused on democracy and Latin America.

“It’s an innovative strategy,” Corrales said. The U.S. wants tangible changes from Venezuela’s regime, but it doesn’t want to send in the Marines, so it outsources stability on the ground to the bad guys—the regime.

“It’s a bit like removing Saddam Hussein but keeping the rest of his government in place,” he said. The big question is whether it will work, he added.

Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodriguez speaks to the press at the Foreign Office in Caracas, Venezuela, Monday, Aug. 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Ariana Cubillos)

For most ordinary Venezuelans, the approach could avoid a bloody civil conflict but it dashes their hopes of a quick transition to democracy or economic recovery. More than a week after the ouster of Maduro, the same corrupt regime remains in place, with armed paramilitary squads roaming the streets. One encouraging sign is that several dozen political prisoners have been released in the past week.

So little has changed in Caracas that the regime is functioning as if Maduro had died from a heart attack rather than been taken prisoner to the U.S., said Eliot Cohen, Trump’s special envoy to Venezuela during his first term.

The strategy is a departure from recent decades, during which U.S.-led forces ousted regimes in Iraq and Afghanistan as part of the war on terror, and in 1989 invaded Panama to topple Gen. Manuel Noriega on drug charges. In all three cases, the U.S. forced the collapse of the pre-existing regime, requiring tens of thousands of U.S. troops to try to keep order and create space for civilians to attempt to help set up a Western-style democracy.

Results were mixed at best: Panama became a stable democracy, Iraq endured a protracted civil war and is now a shaky democracy, and Afghanistan has reverted to the Taliban. The long and messy occupations in Iraq and Afghanistan cost thousands of American lives and cost taxpayers at least $4 trillion, according to estimates by Brown University’s Cost of War project—a cost in blood and treasure that turned many Americans against the idea of exporting democracy. Trump has long said he would avoid that kind of idealistic nation-building exercise.

After decades of aspiring to remake the world along western liberal lines, the U.S. is coming to terms with limits on U.S. power, said John Lewis Gaddis, a professor of military history at Yale University.

“The choice is between accepting that your own power has limits and that you’ll have to learn to live with some bad guys, or risk dissipating your power and the domestic roots that sustain it in the interest of turning the world into one of angels,” he said.

The Trump administration likely concluded that decapitating Venezuela’s entire leadership would require a ground invasion and prolonged military presence, risking fragmentation and violence between rival factions of the military and cocaine-trafficking groups allied with Maduro and his lieutenants, said Hernandez Roy.

A U.S. occupation of Venezuela would likely require at least 100,000 troops, according to John Polga-Hecimovich, an analyst at the U.S. Naval War College who closely tracks American policy in Venezuela. That figure is short of the peak of about 170,000 in Iraq, but far more than the 27,000 used in Panama, a far smaller country.

“Trump doesn’t have the appetite for that, and his base doesn’t have the appetite for that. So the alternative is this,” said Polga-Hecimovich. It also turns out that while the U.S. isn’t very good at nation-building, it is good at the kinds of strikes the Trump administration has rolled out in the past year: bombing Iran’s nuclear facilities and the daring raid that captured Maduro.

Captured Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro arrives at the Downtown Manhattan Heliport, as he heads towards the Daniel Patrick Manhattan United States Courthouse for an initial appearance to face U.S. federal charges including narco-terrorism, conspiracy, drug trafficking, money laundering and others in New York City, U.S., January 5, 2026. REUTERS/Eduardo Munoz

“The military is trained for this type of raid. We are really good at that—and we got to show Russia and China we are really good at that,” he said. The almost made-for-Hollywood raid in Venezuela was also a much easier sell to the American public than being mired on the ground for years, he added.

Absent a U.S. ground force, an immediate transition to opposition figures after the capture of Maduro was deemed unrealistic by the Trump administration because the opposition would have difficulty leading the government and military, which are staffed by regime loyalists.

Trump has said he is open to meeting Venezuela’s acting President Delcy Rodríguez, a regime stalwart who has long been close to Cuba, and said she has been “very good” so far. Opposition leader María Corina Machado, whom Trump has said lacks the clout to manage a transition in Venezuela, is due to meet Trump on Thursday. She is expected to press him on pushing a transition in Venezuela.

Although it doesn’t have boots on the ground, the U.S. has leverage: the threat of more military action against uncooperative regime members and the ability to seize Venezuela’s oil exports to starve the regime of money.

Whether that leverage is enough to press regime leaders to make meaningful changes like an eventual transition to democracy remains to be seen.

The U.S. approach comes with risks. It binds the U.S. to a hard-line group of Venezuelan officials who have wrecked Venezuela’s economy, spent decades working to oppose the U.S., and worked with terrorist groups as well as U.S. enemies like Russia and Iran.

“Venezuela right now is closer to democracy than it was on Jan. 2, but it is also much closer to collapse than Jan. 2,” Polga-Hecimovich said. “Maduro held all these rival factions and competing groups together. Can Delcy do the same? Can she toe the line between obeying masters in Washington and keeping armed Chavismo on the ground happy?”