I think it’s fair to say that, ask any inhabitant of Greece, from the President to the woman on the street, about political developments in the years ahead, and they’ll reply that there are two things they do not know:

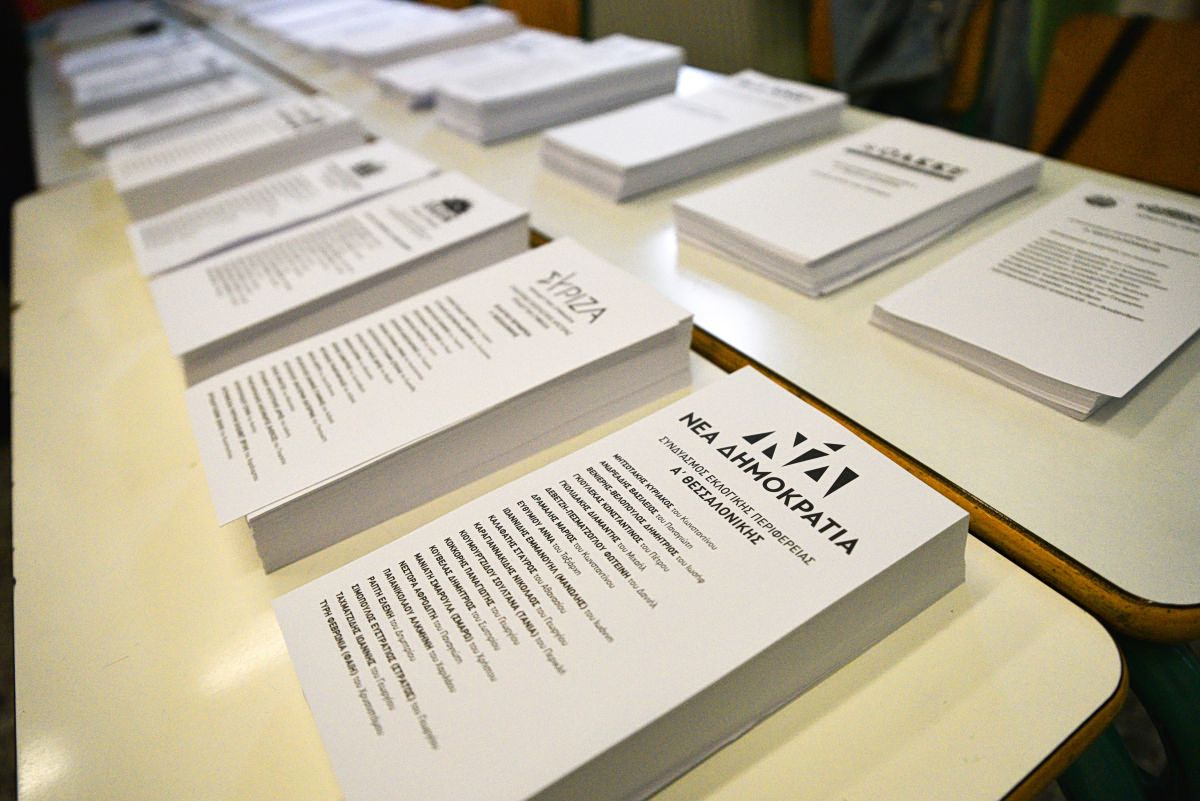

First, whether New Democracy will win an absolute majority in the next elections.

And second, what will happen if they don’t.

And they’d be right to ask themselves both questions. Only an inhabitant of Alpha Centauri could pass them by without a second thought.

But because vanishingly few inhabitants of Alpha Centauri walk among us, I think it’s fair to say we can set their indifference aside.

Oddly enough, though, the citizens of no other European democracy would share their puzzlement if asked the same question. Why would they? Because across Europe, if no one party ends up with an absolute parliamentary majority after the elections, it will collaborate with other parties to rule the land.

Obvious stuff. But out of the question in Greece, where none of the parties want to work with any of the others—or that’s what they’ve said, at least.

It’s not the lack of consensus that’s the blame in this case. It’s the lack of political common sense.

Which tells us (whether the parties are willing to acknowledge it or now) that if ND does not have an absolute majority, and if the numbers don’t add up to a parliamentary majority against it, then a ruling coalition including ND may emerge after the elections.

I mean, is there any other way it could play out? Which is why the parties in other European democracies don’t seek coalitions, either, unless they have to. They roll the idea out when the need arises.

It’s a bit like a safety valve for ensuring political stability—a mechanism embedded into the very logic of democracy.

I repeat that it is not a question of consensus. Because you can only have consensus for a bill or a policy, or the appointment of a President to some Independent Authority.

And, needless to say, a democracy needs consensus along with moderation to function. All yelling does is give everyone a headache. But above all else, a democracy needs down-to-earth political logic.

So where’s the disconnect in Greece’s case? Because I don’t subscribe to “national character defects”, my explanation of choice is that Greece remains in the thrall of a deep-rooted anachronism.

One which constrains the political system to the stature and capabilities of its leading players.

So, it’s the best they can do… and why they don’t cultivate a shared systemic awareness, either. That’s the key ingredient that was missing from last decade’s disaster—and the main lesson.

To be honest, though, I’m not sure the political system has taken it on board . If it has, it certainly doesn’t show it. And as I understand it, a lot of people share my doubts

But “Sunday is a short feast,” as they say. I’ve no doubt it will soon be called upon to prove it.