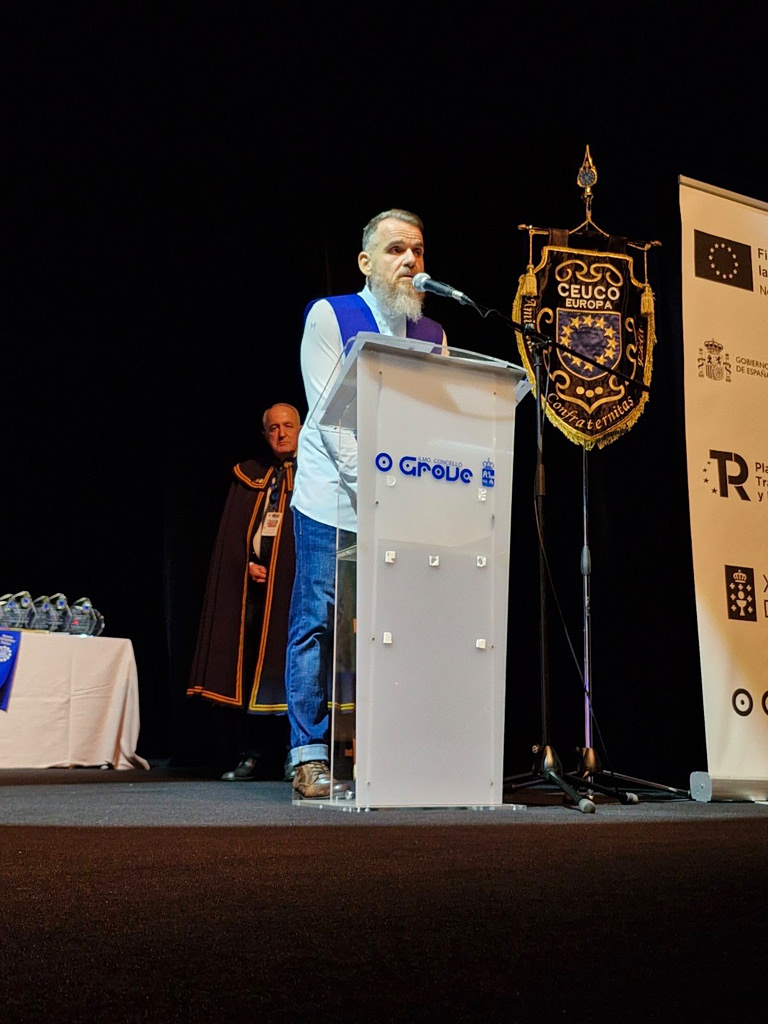

O Grove, Spain – When most people think of Greek hospital food, they picture flavorless mashed potatoes and tasteless soups, meals that sustain but never satisfy. For over two decades, chef Iakovos Apergis has been rewriting that narrative at the Tzaneio General Hospital in Piraeus. His work has not gone unnoticed: on November 29, 2025, Apergis was named “European Chef 2025” by CEUCO, the European Council of Oenology and Gastronomy, at a ceremony held in Spain. The award was presented by CEUCO president Carlos Martin Cosme and vice president Konstantinos Mouzakis.

The distinction, awarded by an organization with over 10,000 members across Europe, challenges conventional notions of where culinary excellence belongs. In an era in which gastronomy is often synonymous with Michelin stars and fine dining establishments, Apergis has proven that exceptional cooking can flourish in the most unexpected places—not despite the constraints of a hospital kitchen, but perhaps because of the deeper purpose it serves.

Apergis never imagined he’d work in a hospital kitchen. “I applied in 2003, but at that time, the idea of a hospital didn’t excite me,” he recalled. That same year, his mother passed away at the Tzaneio. “I lost my mother in March, and in June I was working there; that is how my journey began.” That profound loss became the foundation of his life’s work, a mission to do away with the very concept of “hospital food.”

“There is no such thing as ‘hospital food’,” he has consistently argued. “It is simply food that is convenient to everyone. It’s easier to make unsalted food for everyone, except not all patients need to eat unsalted food.”

Chef Iakovos Apergis prepares ham and cheese pie at Tzaneio Hospital’s kitchen. / Photo courtesy of Iakovos Apergis.

Changing that mindset required more than a philosophy; it required persistence. When he started, the kitchen ran on outdated equipment and old-school thinking. The 2004 Athens Olympics brought an upgrade: “For the first time, I saw new equipment in the kitchen! That’s when we got our chef’s uniforms, too,” he remembered. But that equipment is now over two decades old, with half of it barely functional.The real transformation came in 2010, when a transfer to the Venizeleio Hospital in Crete gave him the space to experiment. “They gave me freedom to do things. I gained my culinary confidence,” he recalls. When he returned to Athens, he brought that confidence back to the Tzaneio and started reimagining hospital cuisine. He began with fish: when children wouldn’t eat it, he transformed it into fish burgers. Then came beef burgers, chicken burgers. “We evolved,” he said simply.

His resourcefulness became legendary among colleagues. When he needed ketchup for burgers one day, he ran to the café next door and asked for it. They gave it to him without hesitation. “I work with what I have,” he explained. “Not having ketchup won’t stop me from getting patients fed.” When the Hilton Hotel in Athens closed, he asked for their plates and silverware to be taken to the hospital. “Patients were eating off dishes and utensils from a five-star hotel,” he recalled. He seeks donations wherever he can find them. “People usually support me,” he said.

Today, working with equipment that requires constant improvisation and repair, Apergis creates meals that would not be out of place in a contemporary bistro. His daily menu might include slow-braised beef stew, whole wheat pasta with mushroom sauce, oven-baked meatballs with potatoes, orzo, briam (Greek roasted vegetables), and braised green beans. But nothing is one-size-fits-all: each dish is adapted to individual medical requirements: pureed textures for dysphagia, modified portions for diabetes, or low-sodium for heart patients. He cooks daily for approximately 240 patients and 120 doctors—160 during on-call shifts.

His impact extends beyond Tzaneio’s kitchen. He teaches at a culinary institute, volunteers at institutions supporting at-risk youth, and consistently advocates for better conditions in hospital kitchens across Greece. He fights to keep hospital kitchens operational rather than outsourced to catering companies, believing that the human touch in cooking matters, especially for those vulnerable. He prepares homemade pizza and cakes for children in the psychiatric unit, taking quality ingredients and transforming them into comfort food young patients will actually enjoy.

In 2023, Apergis authored “Recipes for Cooking & Health”, a practical guide for people with dysphagia—swallowing disorders that affect thousands of patients. The book’s impact extended beyond Greece: at the 2023 Gourmand World Cookbook Awards, it won first place worldwide in the fundraising category and second place in health and nutrition—recognition for both its innovation and philanthropic purpose.

“At the end of the day, I want to provide the best food for all our patients; being a cook in a hospital is definitely worthwhile,” he insisted. The evolution has been gradual but undeniable. “People talk about good hospital food now,” he said, “and that means something.”

What drives him is a simple philosophy: food is dignity. “It’s those 20 minutes that will give you happiness in a cold hospital room,” Apergis said with pride. He recognizes that for patients separated from their families, hospital food can be a much-needed comfort, a reminder of home. His every decision reflects a deep empathy for those he serves.

The CEUCO award, which has previously honored Europe’s best olive producers, restaurants, and culinary innovators, recognizes excellence in all its forms. That it went to a hospital cook this year underscores that exceptional gastronomy is defined not by setting or prestige, but by purpose and dedication.

Photo courtesy of CEUCO.

The road to recognition was rigorous. For two months, CEUCO reviewed videos of his work at the Tzaneio and examined his credentials, including his dual Gourmand Award-winning cookbook. When the organization finally voted, the deliberations lasted 12 hours, a testament to the careful consideration afforded to each candidate.

For Apergis, this recognition validates a simple but radical idea: that everyone, regardless of their circumstances, deserves good food. A patient in a hospital bed has the same right to a well-prepared, flavorful meal as a diner in an upscale restaurant. Working with broken equipment and limited resources, he has shown that exceptional cooking requires only one ingredient: care.

Apergis’ attendance at the ceremony was made possible by the Captain Vassilis and Carmen Constantakopoulos Foundation.