Last Tuesday, the EU Environment Council (ENVI) met in Luxembourg and formally approved the European Commission’s new Water Resilience Strategy (WRS). Although the approval is largely symbolic, the WRS is not. By 2030, global water demand is expected to exceed available resources by 40% and the WRS is Europe’s efforts to ensure a more holistic approach to water management, to promote water security for the bloc, and to be better prepared for water-related disasters.

The Commission has said the WRS will “help the EU improve the way we manage water while making our businesses more competitive and innovative,” setting targets for efficiency, reuse, storage, and data governance, and urging Europe to plan for water “as it does for energy or semiconductors.”

The change in approach is significant, as water resources until now have largely been governed by the Water Framework Directive, which primarily focused on water quality, as opposed to quantity.

“Water is now recognized as a strategic asset for Europe’s sovereignty, resilience, and competitiveness,” noted Durk Krol, Executive Director of Water Europe, a Brussels-based network of 300 utilities, research bodies and companies.

Krol told To BHMA International Edition that Europe’s existing frameworks were written for another era and underlines the need for holistic approaches. “Water quantity is becoming a real challenge for our society—not only from an environmental perspective, but also from an economic one.”

But water scarcity and EU-wide issues such as critical water infrastructure will require tremendous funding to address, as will the transition to circularity and digital means.

Water Europe estimates that closing Europe’s investment gap will require €300 billion under the next EU budget (2028–2034). However, every euro invested in water, it calculates, will yield about €2.35 in economic output while 16,000 jobs will also be created per billion invested—a persuasive case for treating water as critical infrastructure.

Greece on the front line

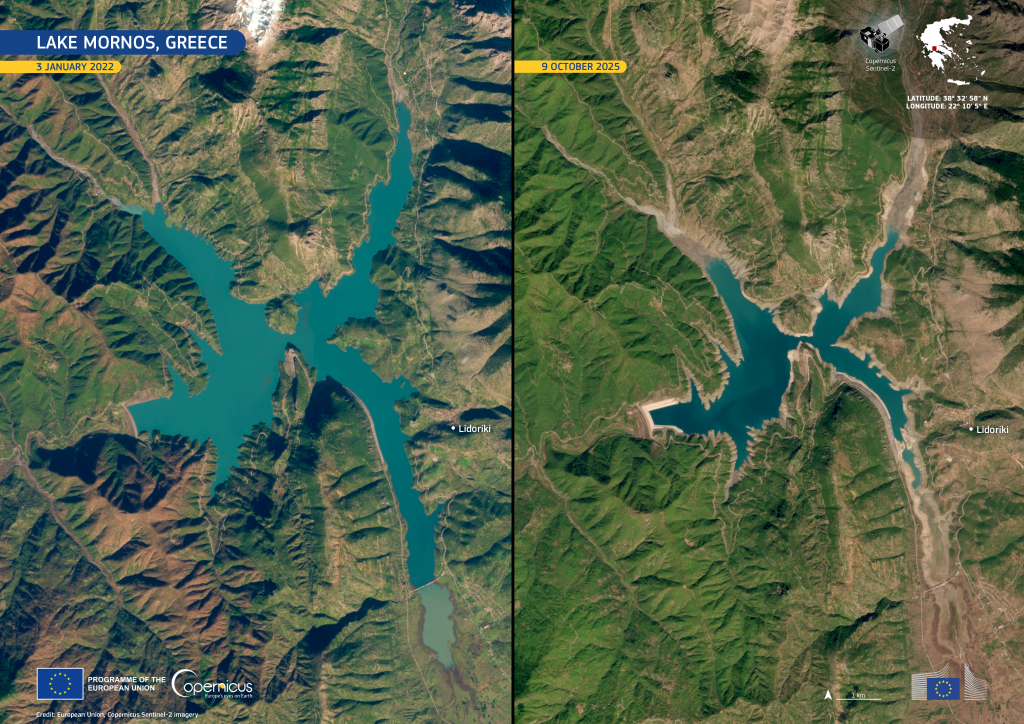

The vote by ENVI comes amid early-autumn rains in Athens, which traditionally ease fears of seasonal water scarcity issues. Yet fresh Copernicus satellite imagery reveals large swathes of southern and central Europe still dry as a bone, Athens’ main Mornos reservoir at dangerously low levels, and soil moisture far below average, reminding us that seasonal rains can neither impact on long-term climate projections nor redress structural and governance problems.

The impact of drought on Lake Mornos, Greece, one of Athens’ main water reservoirs. /European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-2 imagery

The European Environment Agency warns that water stress already affects roughly 20 % of the EU’s territory and 30 % of its population each year, with water stress and scarcity impacting places beyond the Mediterranean, including Belgium, Germany and Poland.

Yet few countries illustrate Europe’s water stress more starkly than Greece. The World Resources Institute ranks it 19th globally for drought risk. National data show rainfall down 10–20 % and Attica’s reservoirs almost 50 % lower than last year.

In July, Athens launched a new National Water Plan—the first full reform in decades. The program, known as YDOR 2.0, will reportedly mobilize around €4 billion through public-private partnerships and assist in the upgrade of irrigation infrastructure, the reduction of water losses and introduction of digital monitoring and reuse.

Watering system with multi directional multiple water supply pipelines in Crete, Greece.

On the governance side, it envisions the creation of regional water authorities, starting in Thessaly, the area hardest hit by Storm Daniel in 2023 and now the third most water-stressed region of Greece, according to Aqueduct.

“If you want to address the water challenges in Europe, the first thing you need to get straight is the governance,” says Krol. “Because if you don’t have the governance correct, then the rest will not work.”

Simplification and consolidation will go a long way, as Greece’s water management is split among hundreds of actors throughout the country, ranging from local municipal authorities to regional operators and national authorities, resulting in a highly fragmented governance framework.

Meanwhile, like Spain, Italy and Cyprus, Greece faces heavy summer demand from tourism and agriculture layered onto fragile infrastructure. “On average, Europe loses about 21 % of the water in its networks,” Krol notes. “In Greece, it’s estimated to be between 50 % and 70 % in some areas.”

Still, there have been some encouraging pilot schemes: the Athens’ Water Lab and digital monitoring in Larissa have drawn attention as “smart” water management models. “We see dynamic and innovative approaches being taken in Greece,” Krol adds.

Innovation, investment, and water quality

Digitalization and circular use stand at the heart of Europe’s strategy.

“Smart metering, leak detection and AI-based forecasting can cut losses rapidly. Reuse of treated wastewater, already practiced in Eastern Attica, should become mainstream across Europe. Desalination powered by renewable energy and advanced brine management offer security for islands and coastal zones,” says Krol.

But Europe’s water future also depends on recognizing that quality and quantity are inseparable. Leaky or overloaded systems don’t just waste water—they allow pollutants to infiltrate aquifers. The recast of the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (2024) now mandates the advanced removal of micropollutants as well as energy-neutral treatment by 2040, binding cleaner effluent directly to resilience.

Europe is slowing learning that safeguarding supply also needs to consider what flows down and out of the drain, and reutilize it through circular means. Attica’s reuse pilots and Spain’s irrigation loops are based on the premise that wastewater reuse isn’t waste management, it is part of holistic water resource management.

To fund the transition, Water Europe proposes a Water Investment Accelerator to blend EU, EIB and national financing with project guarantees for quicker rollout. The European Investment Bank has already pledged €15 billion for water projects through 2027.

Such investments, Krol stresses, deliver rapid returns:

“Water resilience investments are among the most cost-effective forms of climate adaptation. A no-regrets package for Europe includes leakage reduction, reuse expansion, diversified sources, digitalization and improved governance.”

FILE PHOTO: A worker maintains a desalination plant, on the island of Naxos, Greece, June 20, 2024. REUTERS/Stelios Misinas/File Photo

The risk and opportunities ahead

Without acceleration, water could indeed become Europe’s next systemic crisis. Droughts are already cutting crop yields, draining hydropower, and threatening industry. The European Central Bank estimates that escalating scarcity could jeopardize around 15 % of euro-area output by 2030.

Moreover, the bloc’s hopes of catalyzing AI to improve water management, improve overall competitiveness in the EU, and serve as a powerhouse to solve complex problems relies on the ample availability of water to cool data centers.

For Greece, the stakes are existential: shrinking rainfall, depleting reservoirs, heavy reliance on irrigation, and intense water use during the summer months on water-stressed islands all point to structural imbalances. With significant water governance reform, smart-network pilots, and additional desalination plants coupled with renewable energy sources and storage underway, the country could also become a Mediterranean testbed for solutions much of Europe will soon be needing.

The ENVI Council’s approval of the WRS gives the nod to Brussels long-awaited framework, but it also starts the clock. By 2026, Member States must table national drought-management plans, water-efficiency targets, and reuse schemes. Situation assessment and management plans are a step in the right direction, but successful implementation hinges on regional capacity and local delivery, not Brussels’ demands.

Europe’s credibility on water security will depend on its capacity to turn strategy into tangible progress, from smart pipes and sensors to circular networks, net-positive systems and nature-based recovery. From Athens to Brussels to Berlin, Member States share a single responsibility to rebuild the infrastructure that keeps the continent healthy, competitive and secure, proving that water is not a constraint but the foundation of Europe’s future strength.