Obituaries and memorials for paper began being written even before our thumbs were trained in the doctrine of scrolling. It was a memorial with an open invitation: everyone present, holding smartphones instead of flowers, ready to bury newspapers and magazines under tons of free, ephemeral—and not always high-quality—information. The mourning for the end of analog journalism seemed at the time predetermined, absolute, almost inevitable. Today, it feels more like an old trending topic that has simply faded.

It may sound to some like a crescendo of romanticism or even a death rattle, but the more information increases and multiplies online, the more print gains back lost ground. As a premium choice, an experience, even an obsession for younger generations. In a world where we process roughly 100 GB of information daily and consume 105,000 words through screens—a quantity roughly equivalent to 200–300 pages—the printed page returns as a tool for digital detoxification as well as a trust anchor.

This is not speculation or euphemism, but a measured trend. The value of the global publishing market is estimated at $202 billion, confirming that our need to read something that does not emit blue light is also economically measurable.

The neurology of flipping pages

One reason paper is regaining ground is that our minds are tired from the flood of information. Experts speak of digital fatigue, a form of mental and emotional exhaustion caused by endless online presence, leading to anxiety and reduced concentration.

It is notable that 73% of consumers now report being “fed up” with digital advertising. Justifiably, as our daily exposure to information equals the content of 174 newspapers. Print emerges as a new-old challenge: to slow down, to experience, and to connect with content without notifications, distractions, or cries for attention.

There is also something deeper happening in the brain when we scroll. Research shows that screens may favor reading speed but impair comprehension depth. When we read on paper, the brain creates a “mental map.” We remember that the sentence that struck us was at the top left, next to the dog-eared corner of the page. Endless scrolling eliminates the sense of space and time.

And then there is touch. The weight of a publication, even the texture of the paper, functions as neural signals for the brain. Flipping through pages creates the so-called endowment effect, subconsciously increasing the value we assign to the content we read. Neuroscience studies indicate that information on paper is retained up to 70% better and requires 21% less cognitive effort compared to digital reading.

The temples of print journalism

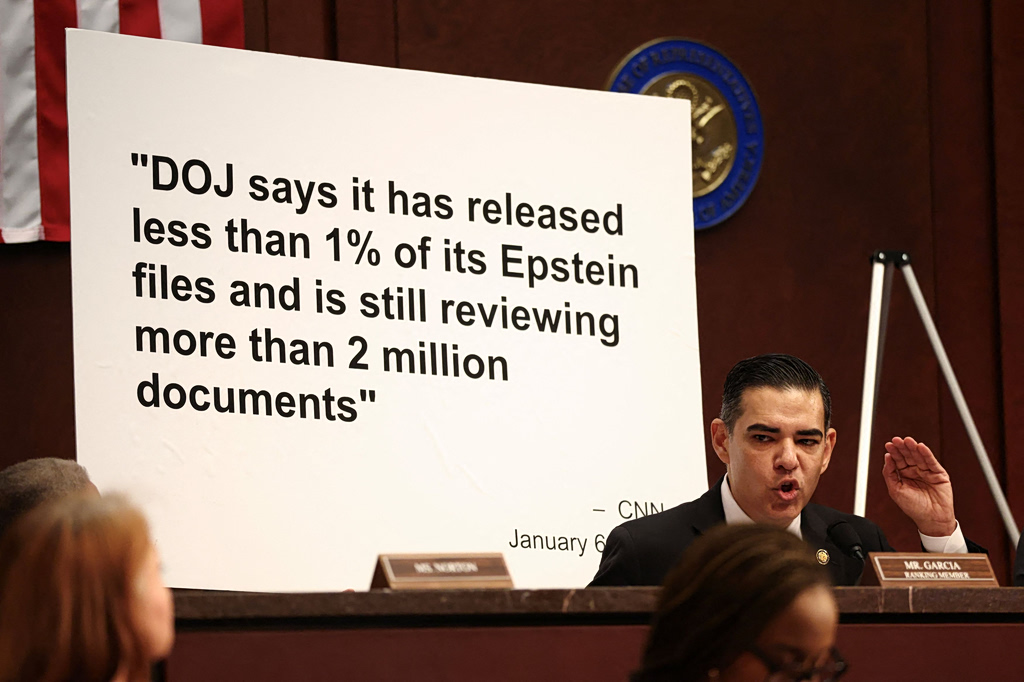

If slow journalism had a cathedral, it would be in Manhattan. The New Yorker, which celebrated its centenary in 2025, reminds us that there is still room for resistance to superficiality. Its obsession with human fact-checking—a costly and time-consuming process, as we saw in the recent Netflix documentary—serves as a moral foundation in an era where automation often precedes accuracy.

In the same vein, Monocle represents a different but related philosophy. Since its founding in 2007, it has built a global news universe based on choice, not quantity. Geopolitics, economics, and design coexist as tools to understand the world. In a digital ocean of information overload filled with fake news hazards, attention to detail glues together a largely fractured trust between medium and reader.

The last of the Mohicans—or not

It is not only glossy pages that continue to attract readers. With 3.8 million weekly print readers and 12.33 million total subscribers, The New York Times continues to invest in print. The trend back to print is even more clearly reflected in the numbers of The Wall Street Journal and Financial Times. The WSJ is now the largest newspaper in the U.S. in print circulation, maintaining over 412,000 loyal paper readers. Its audience—according to research, of higher education and economic level—understands that information you can hold in your hands carries a different weight. Similarly, the Financial Times demonstrates that print journalism has no expiration date, at least as long as it has a monthly readership of 20 million and 3 million subscribers.

The return of the living-dead

No one doubts that from the 2000s onward, paper was the great patient—one with poor survival prospects. But over the past five years, it has shown encouraging signs of recovery. Magazines like VICE, NME, the culinary Saveur, and The Onion have returned—not as mass products, but as premium, subscription-based editions that endure beyond a single reading. Notable is the case of the British i-D, reissued in March 2025 as a biannual £20 edition by the publishing company of former top model Karlie Kloss and her husband Joshua Kushner. The return of the iconic Life magazine, which ceased regular print publication in 2000, has also been announced.

The same path was followed by Nylon, which returned to print in April 2024 after seven years of digital exile. Its new print edition is a high-aesthetic magazine published twice a year, synchronized with major cultural events such as the Coachella Festival. This shift reflects a broader reality: print has become a luxury good. In a market where digital advertising suffers from distrust, paper offers an investment return that even in difficult times reaches 112%.

Reading as a statement of identity

Ironically, the renewed interest in print is not led by boomers or nostalgia-driven readers, but by the oft-celebrated Generation Z. Those who grew up with a bottle in one hand and a screen in the other, spending an average of 6 hours and 38 minutes online daily, are the same generation elevating magazines into a part of their identity.

All kinds of zines, smaller or larger magazine culture festivals such as Milan’s Mag to Mag, and the collectible value of issues from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s are redefining print. It is no longer a declining or museum-bound medium, but a cultural statement.

Yes, paper will never again be the mass medium of the past, nor does it aspire to compete with the endlessly expanding universe of free online information. Yet it will remain with us: as a quiet but solid reminder that thought requires time and responsibility, information requires verification and care, and reading demands the nearly forgotten virtues of concentration and silence.