I might easily have never discovered Zamominia, one of the freshest and most genuinely original Greek bands working with children’s music today. Neither my close circle nor I have children, after all. Friends who work in education, on the other hand, had already seen them live and spoke to me with real admiration about their songs. Yet, against all odds, Zamominia reached me in a far more casual way: during a friendly gathering, when someone mentioned that she and a group of musicians were behind an artistic project organizing “concerts for children”.

My curiosity about this initiative—one that, without my fully realizing it at the time, included a powerful strand of creativity—led me to Pangrati. There, I met Eirini, Giorgos and Alexandros, three members of a collective of musicians, educators and visual artists. With great care and genuine love for what they do, they are creating some of the most thoughtful and high-quality musical works Greek children today are likely to hear.

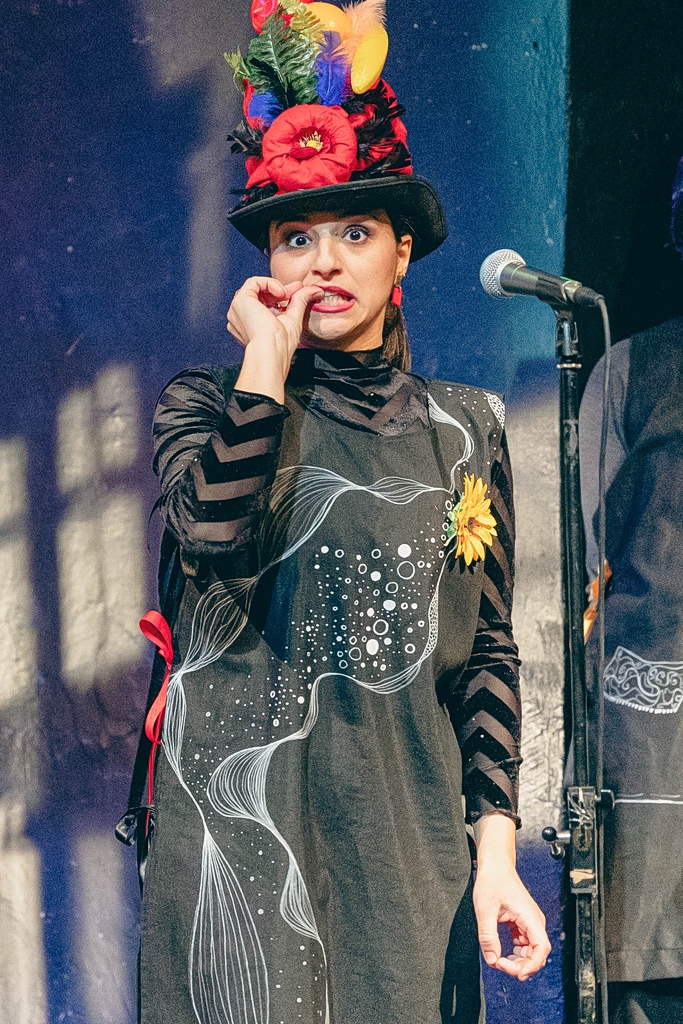

The band comprises five core members—musicians, educators, actors and visual artists covering guitar and vocals, clarinet and flute, trombone, small percussion and saxophone. Photo by Athina Liaskou

Grounded in the needs and interests of children, Zamominia compose and arrange songs, drawing inspiration from jazz, reggae and hip hop, and pair them with their own original lyrics. Their themes range from nature, animals and insects to dinosaurs, strange creatures and whatever else might spring forth from a child’s imagination.

As they explain, Zamonium—where their name comes from—is the only natural element that possesses thought. It exists in the fantastical universe conjured up by the German author and illustrator Walter Moers in The 13½ Lives of Captain Bluebear.

Zamominia during their forest-concerts. Photo by Athina Liaskou

Now celebrating five years since their formation, Zamominia have built a devoted following. Their concerts have taken them from Greek islands to major Athenian festivals, including the Athens Jazz Festival at Technopolis, and to cultural venues including Syntagma Square and the Athens Concert Hall. This holiday season, they return with a Christmas performance at the Poreia Theater on December 29—a lively stage show combining music and movement, original compositions, storytelling, playful energy and a touch of magic.

Just days before the performance, To Vima International Edition introduces this warm, collective-driven, lockdown-born project to its readers through their first-ever print interview. We spoke with Zamominia about who they are, what brought them together, what fuels their creativity, the experiences that shape them on and off stage, and the dreams that guide their ongoing journey.

Illustration by Dinos Dimolas.

Children’s Rhymes Turned into Songs

When and how did Zamominia come about? Who are the people behind it?

Alexandros: Zamominia really began with Eirini. It started from songs she was using with her kindergarten students for music-and-movement activities and musical play. During the Covid lockdown, I’d hear the stuff she was writing and at some point I told her, “If we gather up all this material, work on it properly and arrange it, we could have something really beautiful.”

We have a lot of musician friends, and each of us plays a different instrument. So we started calling people one by one: “Come play drums,” “Come add a viola,” “How about a trombone?” “Let’s record some piano here, a guitar there.” During lockdown, we ended up with at least ten people in the studio—an all-star situation, really.

Eirini: Yes, everything started at the school where I worked with children aged three to six. The pieces emerged directly from the children’s needs and interests as these manifested themselves through play. Sometimes we’d work on monsters, sometimes on shapes, elements from nature or the forest. I’d turn these into rhymes, little songs, even chants. For example, Strange Creatures, which we would later perform at a Christmas celebration, was actually a song designed to help children learn shapes.

Movement Permit: ‘Project Zamominia’

How did your friends react when you invited them to record children’s songs?

Alexandros: It was epic. At the time, you needed official permission just to leave the house. To go out for work, you had to have a document issued by the Ministry of Civil Protection. I still have the copy that says: “Ministry of Civil Protection – Movement Permit for Project Zamominia.” (laughs) Beyond everyone embracing the project, it was incredible simply to be able to go out, enter a studio and make music.

Eirini: Many of us hadn’t seen each other in person for a long time—or hadn’t met at all—because of the lockdown. So that alone made the whole experience very special.

At some point, while Alexandros and I were shaping the songs, I told him that Giorgos should sing them. I’d known him for a while and knew he sang and was incredibly versatile. When he came in to record The Forest and started warming up as we listened from the other side of the glass, we just looked at each other and thought: “That’s it. This is exactly what we need.” It was the first track we recorded vocals for, and I think it really defined the identity of Zamominia.

Giorgos: (laughs) I didn’t know that.

‘Real Concerts’: From the studio to Syntagma Square

How did you go from recording as a group of friends to performing live for children? What do you remember from your first concert?

Eirini: Our first live show took place in December 2021, during the Christmas period, at a café in Nea Smyrni called Deka 4. It was a charity event: instead of tickets, parents and children brought toys for an orphanage.

Everyone who had participated in the recordings was there. After that, people got to know us and started inviting us to different places: kindergartens, creative spaces for children, venues we were somehow connected to.

What I remember most from that first café concert is how happy I was simply because it was happening. I’d never imagined we would end up playing live. It was such a warm and meaningful setting. What we had created in the studio suddenly met its audience—the kids—and there was a beautiful interaction between children and adults.

Alexandros: Honestly, live shows weren’t part of the original plan. I’ll tell you two moments that stayed with me. When we played at the Megaron Concert Hall—our first really big live show—we were a full band. Before we even played the first note, Giorgos came up to me on stage and said, “This is the biggest gig I’ve ever played in my life.” (laughs)

The other memory is of the other Giorgos—Dousos—telling me that once you start doing children’s concerts, there’s no going back, because these are “the real concerts”. And he had a point. Live shows are always demanding, and I won’t pretend otherwise. Even now, after so many performances, there are days when we feel it didn’t quite work.

Giorgos: I remember listening to the recorded songs, hearing incredible musicians—old friends—playing on the arrangements, and thinking, “This is already great.” Then they told me, “Now we’re doing live shows.” Suddenly, we were surrounded by amazing musicians, children’s songs, space for play, and a sense of total freedom. It was ideal—far beyond what I hoped for. It was an intense, uplifting experience playing with these musicians in that setting.

Photo by Marilena Grispou

Music, Movement, Storytelling—and a Singing Mouse

What do children experience at a Zamominia performance? And what can we expect from the Christmas show?

Eirini: Our concerts are built around our songs, but we include activities between numbers: mainly music-and-movement exercises and riddles, so that the children actively participate in the one-hour performance. They play and dance, which keeps them alert; they’re not just sitting still watching five people on stage. There are also costumes—well, hats, really, each one linked to a specific song.

In the Christmas show, storytelling plays a much more central role. There’s an underlying plot: we’re searching for Santa Claus—though we won’t say where he is, because that would be a spoiler. There’s also a magician who joins us as a guest performer, but is fully integrated into the story and the action.

Alexandros: These activities acquaint children with basic musical concepts—soft and loud, slow and fast, pitch, instruments—, and they’re asked to embody what they hear. In fact, at our last show, at the Poreia Theater, something happened which we hadn’t planned at all: at one point, we were playing so quietly that the children lied down! We even turned off the lights and pretended to fall asleep. You can’t rehearse that—it just happens. And I think that really stays with children, while also being incredibly powerful from a music-education perspective.

We have also introduced someone who’s now a full member of the band: Achthos.

Giorgos: Achthos comes from Lyon, the birthplace of Guignol puppetry. I found him one summer when I was there for a concert. I walked into a shop looking for a small puppet and found this character: Achthos Arouris—singer, performer and on-stage personality extraordinaire! I’d been thinking about ventriloquism for years, so I left with Achthos, looked up the technique online—you’re not supposed to move your lips—and the rest is sweat and joy. Training, practice and, of course, the puppet itself.

Vassilis Panagiotopoulos on trombone, and self-taught ventriloquist Giorgos Nikopoulos with his puppet, Achthos. Photo by Athina Liaskou.

A Show That Can Happen Anywhere—and the Joy of the Imaginary

What are the elements that define your group?

Eirini: Trust. When Giorgos suggested bringing Achthos in as a new character in the band, we all immediately felt, “Yes, Achthos belongs with us.” The same thing happened with the magician. Someone could have said, “Let’s meet first, let’s discuss it.” But we feel safe with each other. There’s constant communication, and whatever each person brings to the table is welcome.

Giorgos: At every live show, there’s genuine happiness, exposure and intimacy. Everyone brings their own experience on stage, and there’s a feeling that nothing can really go wrong. For a musician, that sense of absolute safety is extraordinary.

When I first brought Achthos back from Lyon, I hoped I could somehow introduce him to Zamominia. Now, we never rehearse without him. The fact that children believe in him makes him even more real. He’s like my instrument now.

Both in animation, which I studied, and with Achthos, there’s something very primal at work. I think it’s a fundamental human need: to convince ourselves that there is an elsewhere, a parallel, imaginary world. That belief produces a kind of pleasure, as it does in literature and music. Zamominia is exactly that: we first convinced ourselves that we are not just ourselves, but also creatures of this imaginary world.

Alexandros: I’d add that Zamominia and our concerts have a sense of simplicity and folk accessibility. We don’t need elaborate sets, specialized venues, complex lighting or sound. What we do at the Poreia Theater, which is a beautiful space, we could also do right here, right now. We’ve done it in forests, at electricity-free outdoor “forest concerts” which respect nature, and lost nothing in terms of theatrical value. I love that. Even as the creativity and imaginary elements grow, Zamominia remains grounded, something you can take anywhere.

View this post on Instagram

‘A Continuous Album’

What is it like to create children’s music? What inspires you, and what are your dreams for Zamominia?

Alexandros: I deeply love the Froutopia and Lilipoupoli projects. I don’t think they directly influenced my composing, but I have enormous respect for the quality of the work behind them. Platonos, Kypourgos, Maragkopoulos—they approached children’s music with the same seriousness as Pink Floyd approached theirs. That, to me, is the real inspiration: how seriously you take your work.

I also see a gap in children’s music today. When the main contemporary references are just us, Burger Project or The Lazy Dragon, that doesn’t feel like enough. Low-quality productions as we’ve seen in kids’ TV channels, not only create generations of poor listeners, they also fail to honor the responsibility we have toward children—a responsibility that is inherent in children’s music.

What I dream of, as with most things in my life, is movement. Not settling into a formula. As long as there’s motion, I feel alive.

I like to think of Zamominia as a “continuous album”: a concept that keeps evolving. Everything we do adds to what already exists. A new song becomes part of the album, part of our YouTube catalog. It all keeps growing.

Eirini: From my work with children, I’ve seen how profoundly they are affected by art—and how much difference quality makes. I really like where we are right now, the imaginary world we’ve built. I’d love for us to perform more and to open up to schools where children may not otherwise have access to experiences like this. I also hope that our imaginary universe continues to grow. We’ve already enjoyed the musical aspect immensely; the fact that something is always being added, that we each keep bringing something new at just the right moment, works beautifully for us.

Giorgos: I look at the works that have been written and developed within this framework—Zamominia—and I count the years: five so far. Then I think, what about ten? What about creating a collective work together in another medium? Which, in a way, is already happening. I think the process moves forward on its own.

I mean, we create performances, we make records, so we could just as easily develop a series of episodes or even a film. Ours is a space of infinite capacity.

Multiple parts of our collective imagination are currently working on how this world might expand: what new elements we could bring in—the magician, new instruments, new ideas, new lyrics. We watch performances together; we are a community, a collective. That isn’t a given, but we share a lot of love, and that’s how creativity has found a channel and continues to nourish this space.

At the same time, because the project is self-managed, there’s something anti-marketing about it. There are no managers, no record labels, none of those pressures so many artists face—“in five years, you have to have done this, and this and this…” Everything comes from within the group, naturally and unforced, and that allows us to protect a way of working that feels honest. That, to me, is what our work is really about: freedom.

Saxophonist and vocalist Theodosia Savvaki. Photo by Marilena Grispou

Zamominia are primarily comprised of:

Eirini Dimaki (lyrics), Alexandros Dandoulakis (guitar, vocals, composer and arrangements for all songs), Giorgos Dousos (clarinet, flute), Giorgos Nikopoulos (vocals, small percussion), Vassilis Panagiotopoulos (trombone), Theodosia Savvaki (vocals, saxophone).

Τhe band’s name derives from the book’s Greek translation and the term Zamomini , by Maria Aggelidou (Agra Editions).

You can hear more songs of Zamominia here. Tickets for the band’s Christmas show can be purchased here.