KLAIPEDA, Lithuania—Germany’s top military officer, Gen. Carsten Breuer, stood astride a map of Lithuania laid out on the floor of a makeshift command post in this port city on the Baltic Sea.

A chill rain beat against the windows as Breuer and his aides reviewed plans to surge ammunition and fuel to an armored brigade positioned in the likely path of any Russian ground attack on NATO.

“We need to train where and how we will fight,” Breuer told the camouflage-clad soldiers gathered around him. “We need to be agile. We need a new mindset.”

Breuer is racing to prepare Germany’s armed forces for war. And for the 61-year-old veteran of conflicts from Kosovo to Afghanistan, the clock is ticking.

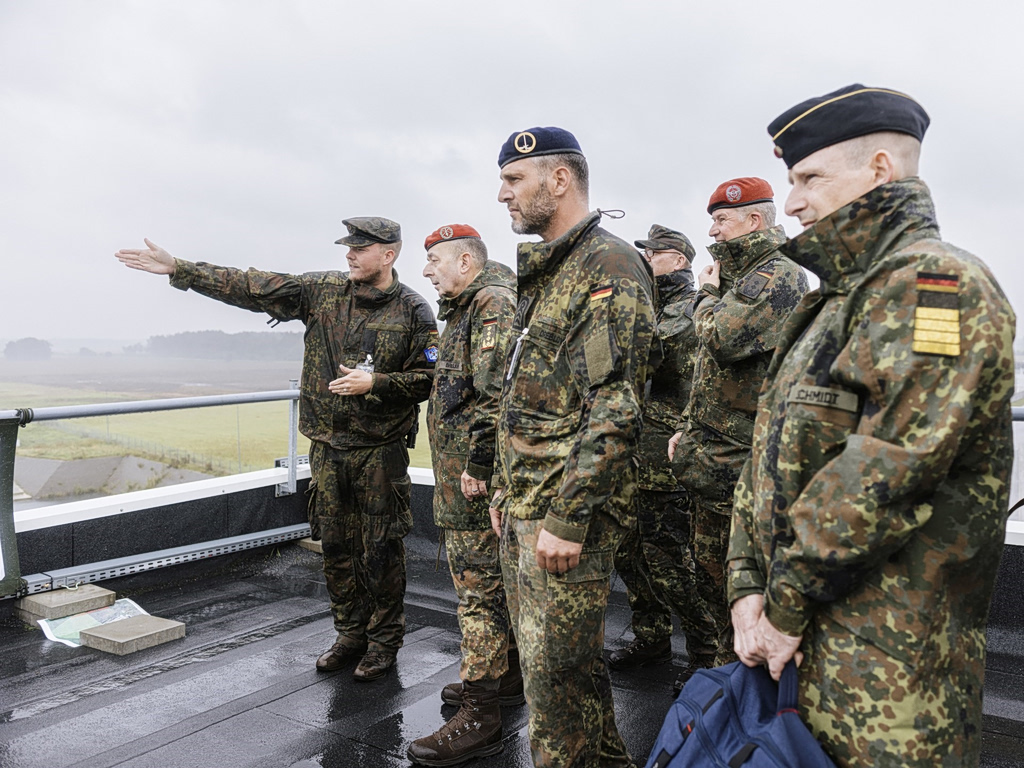

Breuer, 61, is in the vanguard of European generals and national-security officials working to rebuild the continent’s militaries. Patrick Wack/Inland for WSJ

Germany’s military-intelligence agency estimates that within the next three years, Russia, whose armies poured into Ukraine in 2022, will have amassed enough weaponry and trained enough troops to be able to start a wider war across Europe . Breuer says a smaller attack could come at any time.

“We have to be ready,” he says.

To that end, Breuer has been waging a multi-front campaign to rally Germany’s politicians, business people, soldiers and the general public behind efforts to speed the nation’s rearmament and persuade them that they must be prepared to fight Russia to preserve their democratic freedoms.

Defense spending has climbed sharply. And Parliament in December passed a law that will require young men to undergo medical exams to assess their fitness for military service. The aim is to spur voluntary enlistment. Conscription could be next, the government says, if the army doesn’t get enough recruits.

All of this has put Breuer in the vanguard of European generals and national-security officials working to rebuild the continent’s militaries—weakened by years of threadbare budgets after the demise of the Soviet Union—as the threat emanating from the Kremlin has grown steadily more menacing.

On Thursday, German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius nominated Breuer to serve as the next chair of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s military committee. If chosen, he would become principal advisor to the alliance’s secretary general.

Complicating matters is the fact that under the Trump administration, the U.S., for decades Germany’s—and Western Europe’s—most important ally, is increasingly seen as, at best, an unreliable partner and, at worst, a hostile force undermining the continent’s security.

European officials say they need to be prepared to go it alone in the event of war with Russia—a conflict that would define the future of the democratic West. And Germany, the European Union’s largest economy and most populous country, is absolutely central to the continent’s defense. Ironically, a powerful German military, the bane of Europe in the first half of the 20th century, is now essential to its security in the 21st.

The Art of Kriegstüchtig

Kriegstüchtig is the German word for war-ready. Breuer has made this his rallying cry as he drives change in the armed forces and tries to jolt Germans from their post-Cold War, end-of-history reverie.

He and Pistorius deliberately use the term, which carries extra weight in German. Unlike in American English usage, where war is waged on everything from drugs to poverty, the Germans reserve Krieg for armies fighting armies. And it plucks a nerve in a country still scarred by its history of militarism.

Breuer has been waging a multi-front campaign to rally Germany behind efforts to speed the nation’s rearmament and persuade them that they must be prepared to fight Russia to preserve their democratic freedoms. Patrick Wack/Inland for WSJ

Breuer joined the army in 1984, at a time when the military was near its post-World War II peak in terms of troop strength and readiness, with around a half a million men under arms and roughly 2,000 main battle tanks. At the time, it was the mainstay of NATO’s conventional forces in Central Europe.

When the Berlin Wall came down and the Soviet Union collapsed, the need for a large standing army seemed like a thing of the past. German soldiers still fought, including in Afghanistan, where they were part of a NATO-led stabilization force. But military budgets shrank and money was spent on reunification.

By the 2010s, the military was less than half its Cold War size and much of its weaponry and equipment were in disrepair. Over time, Breuer says, “the country that was home to Clausewitz and von Moltke” ended up with few people “thinking about grand strategy.” Breuer was part of a generation of officers whose mission was often to make do with less, focusing on “downsizing and making things more efficient,” he says, “not more effective.”

His job now is to change that.

Breuer’s evangelizing has made him an important public figure in a country unaccustomed to seeing and hearing from men in uniform. On TV, at town halls and universities, the bespectacled officer, with close-cropped gray hair and an almost professorial demeanor, lays out the stakes for his countrymen.

His message is reasoned, calm and direct. He ticks through a list: Russia’s economy is on a war footing; the country is stockpiling artillery shells and tanks; it’s looking to expand its ranks to 1.5 million men.

“We need to be very focused on deterring and defending against Russia,” he says.

That means contending with German society’s deeply ingrained pacificism, a legacy of ruinous wars and the horrors of the Holocaust.

When the German army was reconstituted in the 1950s, firmly under NATO control, soldiers were taught to be “citizens in uniform” and to be fiercely protective of democratic institutions. They were schooled in domestic and international law.

Breuer’s formal title is Inspector General, which makes him sound more like an auditor than a warrior, even though he is the equivalent of the U.S. chairman of the joint chiefs of staff.

The building where he works in Berlin is also the site of a memorial to German officers executed for plotting against Hitler. Looking down into the atrium outside his office, you see a large carpet woven to look like an aerial photograph of bomb-ravaged Berlin at the end of World War II.

“It’s our duty to make sure this never happens again,” Breuer says.

Claudia Major, a political scientist and specialist on German security policy, says Breuer is the perfect messenger because of his thoughtful and deliberate manner. “He manages to explain the dangers to the public without causing panic,” but also without pretending “things are lovely and nice.”

“He doesn’t freak people out,” says Major.

Attitudes have shifted considerably since Russia seized Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 and then, in 2022, launched a large-scale invasion, which Germany’s chancellor at the time, Olaf Scholz, called an “epochal shift.” In 2025, about two-thirds of Germans saw Russia’s military as a threat, according to a defense ministry survey.

Germany is stationing an armored brigade in Lithuania—the first German troops and tanks to be permanently based abroad since World War II. Patrick Wack/Inland for WSJ

The survey also found that 64% of Germans think defense spending should be increased, compared with 57% in 2024. Another 65% think Germany should have larger armed forces, up from 58%. Meanwhile, the perception of the U.S. as a dependable ally dropped sharply, to 37% in 2025 from 65% a year earlier.

In another landmark, Germany is stationing an armored brigade in Lithuania—the first German troops and tanks to be permanently based abroad since World War II. The 45th Panzer Brigade’s 5,000 men should all be deployed by the end of next year.

Already, German tanks and armored personnel carriers, emblazoned with the military’s black Iron Cross insignia, are training in Lithuania’s Rudninkai forest close to the border with Belarus, Russia’s closest ally.

Not Yet War, But No Longer Peace

Europe, in Breuer’s view, is now in a liminal state—not yet at war, but no longer at peace. Governments are contending with near-daily drone intrusions, cyberattacks and an intensifying campaign of sabotage against railways, communications cables and other targets, all of which they blame on Moscow.

The week Breuer visited the German troops exercising in Lithuania, more than a dozen Russian drones violated the airspace of neighboring Poland . NATO fighters were scrambled to shoot them down, and Breuer had to interrupt his trip for urgent consultations about reinforcing the alliance’s eastern flank.

Meanwhile, across the border in Belarus, thousands of Russian soldiers were conducting maneuvers alongside their Belarus counterparts that included planning for the joint use of nuclear weapons.

“We are being tested,” Breuer says. “They are looking for ways we are vulnerable.”

The war in Ukraine, now about to enter its fifth year, is a daily reminder of the menace to the east. On a recent visit, Breuer saw a long convoy of military ambulances carrying wounded men back from the battlefield. “It always comes down to the soldier on the front lines,” he says. “They do our fighting.”

Breuer’s focus on fighting men and women is guiding his sweeping remake of the German military. His task is to lead a pivot back to a military capable of waging and winning large-scale conventional war. The goal is to field three fully equipped combat divisions by 2032.

Breuer and his aides are working with German defense companies to speed weapons manufacturing. “We need to speed up and shorten the innovation cycle,” he says, pointing to the situation in Ukraine where front-line units and manufacturers collaborate to improve weapons on the fly.

Frustrated with the pace of change, last year, Breuer started to give money directly to battalion and brigade commanders so they can buy off-the-shelf commercial drones and other equipment so they can experiment. In the future, Breuer predicts, “Every rifleman will need to be a drone pilot.”

Lt. Col. Tobias Tiedau, a German officer who until recently led NATO’s multinational battlegroup in Lithuania, says units in the field are already benefiting, with new command-and-control and battle-management systems. And he has been buying drones so his men can train with them.

Lt. Col. Tobias Tiedau, a German officer who until recently led NATO’s multinational battlegroup in Lithuania. ‘We are adapting to a new kind of warfare,’ he says. ‘You need to give officers the flexibility to push that through.’ Patrick Wack/Inland for WSJ

“We are adapting to a new kind of warfare,” Tiedau says. “You need to give officers the flexibility to push that through.”

Breuer has also quickly assembled drone-defense teams of 30 to 35 personnel equipped with jammers, radar and counterdrone drones. In early November, when there were drone incursions in Belgium, the defense minister requested help. Breuer sent a team that day and it was operational the next day. A unit was also sent to Denmark.

“That is huge. To have action—and fast—that is a big change,” says Rob Bauer, a Dutch admiral, now retired, who was chair of the NATO military committee from 2021 to 2025. “If you are able to organize something like that in a day, that’s something. The German armed forces were big, but not ready. He’s working on that.”

Filling The Ranks

Another challenge is filling the ranks. The military now numbers about 184,000 men. Breuer is aiming to add another 20,000 men this year and then another roughly 60,000 more by 2035. That force would be supplemented by 200,000 reservists.

Parliament has approved a law that requires all men aged 18 to complete a military- service questionnaire; starting in 2027, they will be expected to undergo physical exams to determine whether they are fit to join.

The hope is that this will prompt more people to volunteer to serve. If the military still falls short of its manpower needs, politicians say, they may resort to compulsory military service, which was suspended in 2011.

Breuer speaks regularly to young Germans. They are one of the toughest groups to persuade that the Russian threat is real, that German society needs to mobilize and that they need to be prepared for military service. It is a tough sell in a country where pacifism is a deeply ingrained civic value.

Breuer at the University of Mannheim in southwest Germany, where he told students that strength was the way to maintain peace. Marc Krause for WSJ

Youth opinions are in flux. A 2025 Ipsos poll conducted for the military found that 42% of Germans aged 16-29 supported new military-service requirements. Another survey found 59% said they probably or definitely wouldn’t take up arms to defend their country.

At an appearance at the University of Mannheim in southwest Germany, Breuer, in his gray-jacketed dress uniform, sprang from his chair, transforming what had been an avuncular presence into one of studied intensity.

“Can we fight a war?” Breuer asked the audience, which responded with surprised laughter. “Are you ready for war?” he said, pointing to a young woman seated near the stage. “Does the question disturb you?” he continued in a series of staccato questions. “What would it be like if Germany was at war?”

Breuer told the students that strength was the way to maintain peace. “We have to make sure that we in Germany are not vulnerable, that we can’t be attacked and that a possible aggressor knows an attack isn’t worth it.”

During the question-and-answer period, one student said “in the end war only leads to people dying” and asked whether all the money now being devoted to defense would be better used to “promote democracy or other initiatives in Russia.”

“If peace is achievable, we must do everything to attain it,” Breuer responded, but he cautioned that years of engagement with Russia and Berlin’s commitment to a change-through-trade policy had failed to keep the Kremlin on a peaceful and democratic path.

Then there is the biggest challenge: contending with the strains now wracking the trans-Atlantic alliance. The Trump administration has criticized allies, cut back on aid to Ukraine and expressed an openness to improving relations with Russia and its autocratic leader Vladimir Putin.

So far, Breuer says, military-to-military relations remain strong. And NATO, under its American commander, continues to operate as usual, parrying Russian threats. “There’s a lot of trust among soldiers,” Breuer says. “Every one of us sees the value in these relationships.”

Breuer has made Kriegstüchtig, the German word for war-ready, his rallying cry as he drives change in the armed forces and tries to jolt Germans from their post-Cold War, end-of-history reverie. Patrick Wack/Inland for WSJ

Breuer was studying at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., on Sept. 11, 2001, when al Qaeda terrorists hijacked planes and used them to attack New York and Washington.

He says it was a seminal moment in his life and one that set the course for decades of his military career, as Germany joined the U.S. in its global war on terror.

Behind the military’s Berlin headquarters building, there is a memorial to the more than 3,000 military and civilian members of the German armed forces who have lost their lives in the line of duty. Fifty-nine of the dead were killed in Afghanistan.

“When I need a moment for myself, when there are really hard decisions, I like to go there to get my head straight,” Breuer says. “In the end you see why you are doing this—for a stable and bright future for all Germans.”

Write to Gordon Fairclough at Gordon.Fairclough@wsj.com