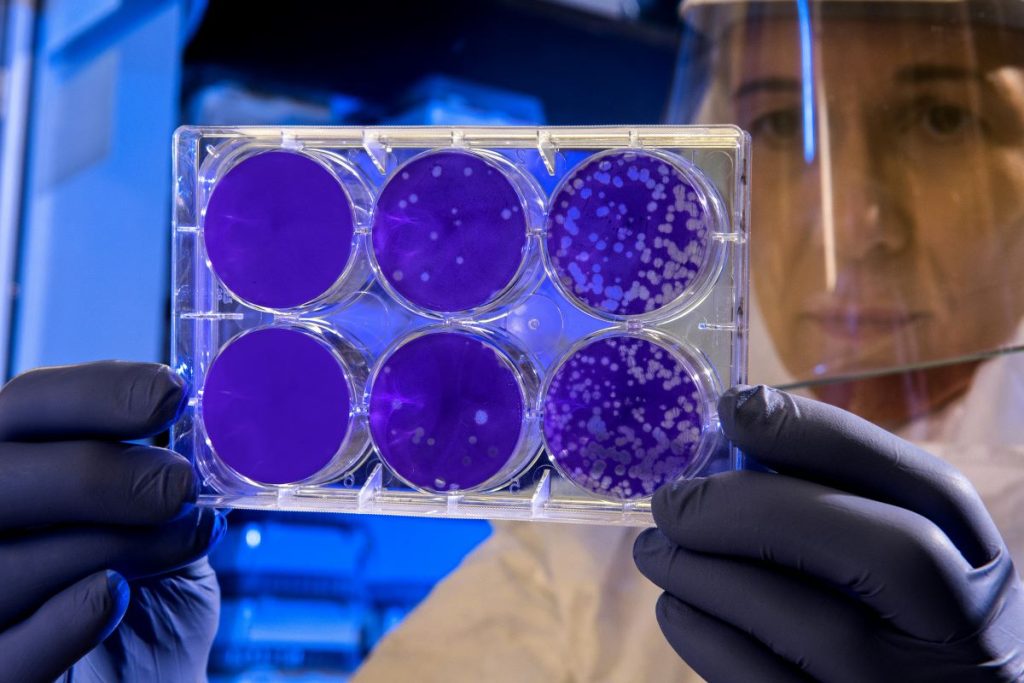

A groundbreaking study from the University of Massachusetts Amherst has shown that a new nanoparticle-based vaccine can successfully prevent three of the most aggressive and treatment-resistant cancers in mice: melanoma, pancreatic, and triple-negative breast cancer.

According to the research, published in Cell Reports Medicine, 88 percent of vaccinated mice remained tumor-free depending on the cancer type, and the vaccine not only reduced the spread of cancer but, in some cases, completely prevented metastasis.

The vaccine works by harnessing the power of nanoparticles engineered to activate the immune system through multiple pathways, while simultaneously targeting cancer-specific antigens. “By engineering these nanoparticles to activate the immune system via multi-pathway activation that combines with cancer-specific antigens, we can prevent tumor growth with remarkable survival rates,” said the study’s lead author, biomedical engineer Professor Prabhani Atukorale.

This new finding builds on previous work by Atukorale’s team showing that their nanoparticle platform could shrink or even eliminate tumors in mice. For the first time, however, the researchers demonstrated that the same approach can prevent cancer from developing in the first place.

In one key experiment, the team paired their nanoparticle system with melanoma-specific antigens—small peptides that mimic the body’s exposure to cancer cells. The vaccine trained immune cells known as T cells to recognize and attack melanoma. When the vaccinated mice were later exposed to melanoma cells, 80 percent remained tumor-free for the duration of the 250-day study. By contrast, all unvaccinated or traditionally vaccinated mice developed tumors and survived no longer than 35 days.

The nanoparticle vaccine also proved powerful against metastasis, halting the spread of cancer to the lungs—a major breakthrough given that metastasis is responsible for most cancer deaths. Atukorale described this as the vaccine inducing a kind of “immune memory,” enabling the body to recognize and eliminate cancer cells throughout the system, not just at a single site.

In a second phase of the research, the team expanded their testing to target additional cancers. They used killed tumor cells (a mixture known as tumor lysate) rather than tailored antigens, allowing the vaccine to be applied more broadly without complex genetic customization. When vaccinated mice were later exposed to melanoma, pancreatic, and triple-negative breast cancer cells, the results were striking: 88 percent rejected pancreatic tumors, 75 percent rejected breast cancer, and 69 percent rejected melanoma. None of these mice developed metastases.

“The tumor-specific T-cell responses we were able to generate were the key to survival,” said co-author Griffin Kane. “This formulation triggers a powerful immune activation that drives the body’s own cells to recognize and destroy tumors.”

Central to the vaccine’s success is its “super-adjuvant” design—a lipid-based nanoparticle formulation that safely delivers two distinct immune-boosting substances in a stable, coordinated way. This design mimics how the body naturally recognizes and responds to pathogens, sending multiple “danger signals” that prime the immune system for a stronger, more lasting defense.

The researchers believe this platform could pave the way for both therapeutic and preventive cancer vaccines, especially for individuals at high risk of developing cancer. They have already launched a startup, NanoVax Therapeutics, to help translate the discovery into clinical applications.

Their next goal is to adapt this technology into a therapeutic vaccine designed to treat, rather than just prevent, cancer. Further studies will determine how these promising results in mice can be replicated in humans—but for now, the findings offer a glimpse into what could become one of the most significant advances in cancer prevention science.