Two sanctioned oil tankers shut off their transponders earlier this month and powered to a meetup point, drawing alongside each other in the Sea of Japan.

The crew of one of the vessels, known as the Kapitan Kostichev, then emptied 700,000 barrels of Russian crude into the tanks of the other, the Jun Tong, according to ship-tracking service Kpler.

The clandestine ship-to-ship transfer, visible via satellite and other shipping data, is a maneuver typical of the shadow fleet, an armada of aging tankers that crisscross the world, smuggling illicit oil for sanctioned nations including Venezuela, Russia and Iran.

The fleet’s operations came into sharp focus this week when U.S. Special Forces dropped from helicopters onto the deck of the Russia-flagged Marinera in the Atlantic Ocean south of Iceland. The tanker, which days before was sailing under a false flag and going by the name Bella 1, was escaping Trump administration action against vessels carrying Venezuelan oil. It had a Russian naval escort and wasn’t carrying any oil when it was captured Wednesday.

Western powers have imposed increasingly severe sanctions to suffocate the smuggling network, but Wednesday’s action—the latest in a recent string of assaults against the shadow fleet—demonstrates a more decisive approach to stamping it out.

Here’s how the shadow fleet works

Russia, Iran and Venezuela have amassed a fleet of old tanker ships to move sanctioned barrels of oil products around the world—or use as floating storage at sea.

Ship operators go to elaborate lengths to disguise the origin of their cargo and avoid detection, changing vessel names and spoofing their locations. They do the latter by falsifying GPS coordinates, using fake vessel names and duplicating transmissions to create ghost ships. On Wednesday, U.S. forces also boarded a tanker near the Caribbean that was broadcasting its location as being close to Nigeria at the time.

What are the numbers?

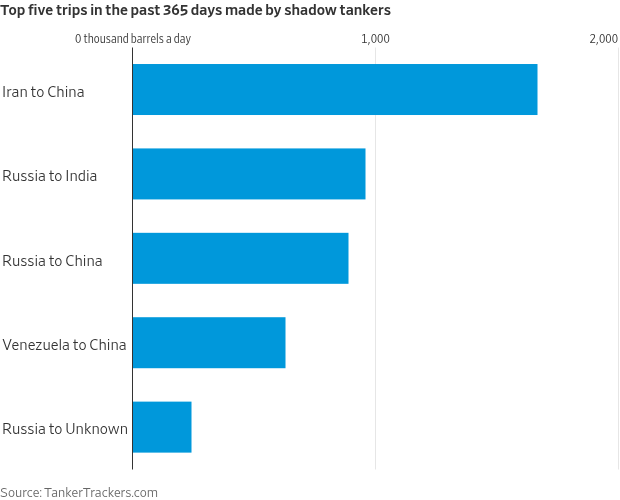

There are now more than 1,470 tankers classed as being part of the shadow or dark fleet, according to the ship monitoring website TankerTrackers.com . Their number has swelled since 2022 as Russia has looked for routes around Western sanctions for its war against Ukraine.

S&P Global puts their numbers at 940, which represent 17% of tankers currently transporting oil, oil products and chemicals around the world.

The shadow fleet transported some 3.7 billion barrels of oil in 2025, accounting for 6% to 7% of the annual global crude oil flows, according to Kpler.

How do the ships disguise themselves?

After unloading its cargo in the Sea of Japan, the Russia-flagged Kapitan Kostichev reappeared on shipping radars on Tuesday, heading back toward the port serving Sakhalin I, the giant offshore oil project in the frozen waters of Russia’s far east from where it initially set out.

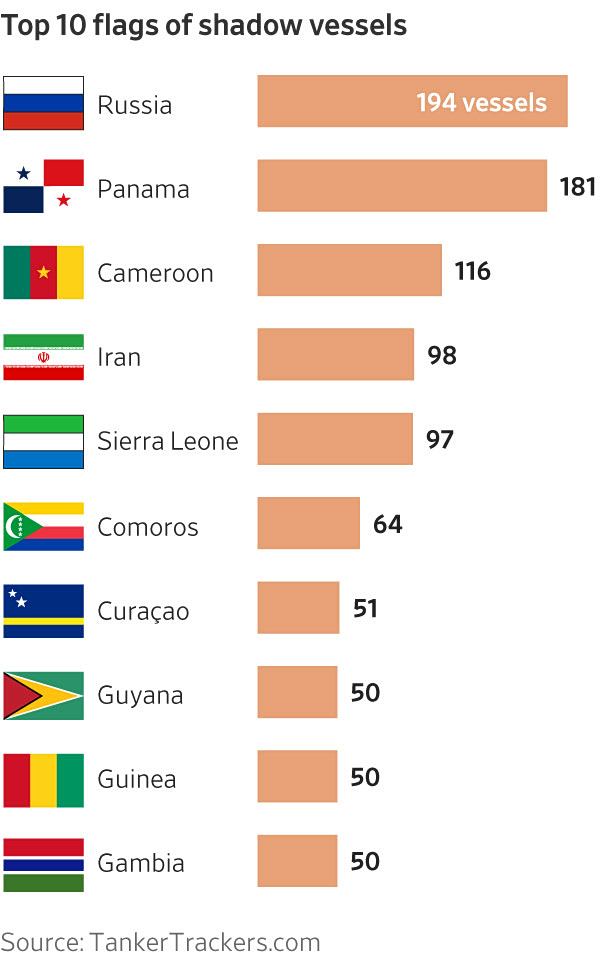

The Jun Tong, known as the Fair Seas until January 2024 and the Tai Shan until August, set a course for the Chinese port of Yantai. China, the world’s largest importer of crude , is also the biggest buyer of Russian oil. The vessel currently sails under the Cameroon flag but has in the past adopted the flags of Malta, the Marshall Islands and Panama.

International maritime law requires every ship to be registered with a specific country—a flag state—granting it nationality. The ship’s flag subjects it to that country’s laws for safety, technical issues and social matters relating to the crew. This registration, handled by a registry, provides legal proof of ownership and requires the ship to carry official documents and display the flag of its registration.

A shadow tanker often uses a “ flag of convenience ” provided by smaller, non-Western nations such as Gabon, Comoros or Cameroon. Flag states’ ship registries are responsible for recording ship ownership and loans secured against vessels, as well as investigating incidents.

In return, the shipowners pay fees. Some small states outsource their shipping registry to third parties. They have also been known to offer sweeteners to shipowners, such as cheaper registration fees, lower taxes and less stringent checks.

The minimal oversight allows shadow tankers to sidestep a global system that was designed to ensure ships are properly insured and crew members well treated.

But when incidents do happen, the smaller flag states don’t always come to the rescue of the vessels sailing under their jurisdiction.

Many of these ships frequently change their names to allow them to evade scrutiny. For example, the oil tanker that was seized in the Atlantic on Wednesday was renamed to the Marinera a few days after the U.S. Coast Guard began pursuing it in December. Its past monikers include the Neofit and the Yannis, according to Singapore-based maritime intelligence company MagicPort. The ship claimed Russian protection after the crew sloppily painted a Russian flag on the side of the vessel.

What other features distinguish the fleet?

Around one-third of the tankers involved in the shadow fleet are more than 20 years old, according to TankerTrackers.com, making them prone to major accidents. Many lack reliable insurance.

Most of the world’s ships are insured and reinsured in Europe. Western sanctions have banned most insurers from providing services to these ships, cutting the vessels off from Western insurance markets. As a result, some use non-Western insurers or sail without coverage.

Who owns its ships?

Shadow-fleet vessels typically change ownership multiple times, relying on shell companies in places with loose registration regulations such as Dubai, Hong Kong and the Marshall Islands, to disguise the identities of their ultimate owners.

What action has been taken to stop the fleet?

Aside from the U.S. action against Venezuelan oil and sanctions of the tankers themselves, Ukraine went after the Kremlin’s shadow fleet in international waters last year for the first time during its war with Russia. In November, Ukraine’s navy and SBU security service used drones to attack two tankers in the Black Sea that had been sanctioned for carrying Russian oil.

The explosion of sanctions in the Russia-Ukraine war, and the money to be made from circumventing them via shadow vessels, has shown the limits of Western sanctions, said Nathanael Kurcab, a partner at law firm Morrison Foerster’s National Security Group.

“We’re now having to do almost what sanctions were never supposed to require, which is using military assets to enforce the blockade of Venezuela. That’s brand new,” he said.

Write to Rebecca Feng at rebecca.feng@wsj.com , Matthew Dalton at Matthew.Dalton@wsj.com and Daniel Kiss at daniel.kiss@wsj.com