New Year is a time when people wish each other the best for the year ahead and predict what it’s likely to bring.

We’re fine, we haven’t done too badly so far. But it would be dishonest of me not to note that the big question mark hanging over 2026 isn’t the farmers’ protests, but rather our relations with Turkey.

And it wouldn’t be entirely honest of me not to add that the question mark looms even larger in an international environment that has yet to settle into a new status quo and remains profoundly unpredictable.

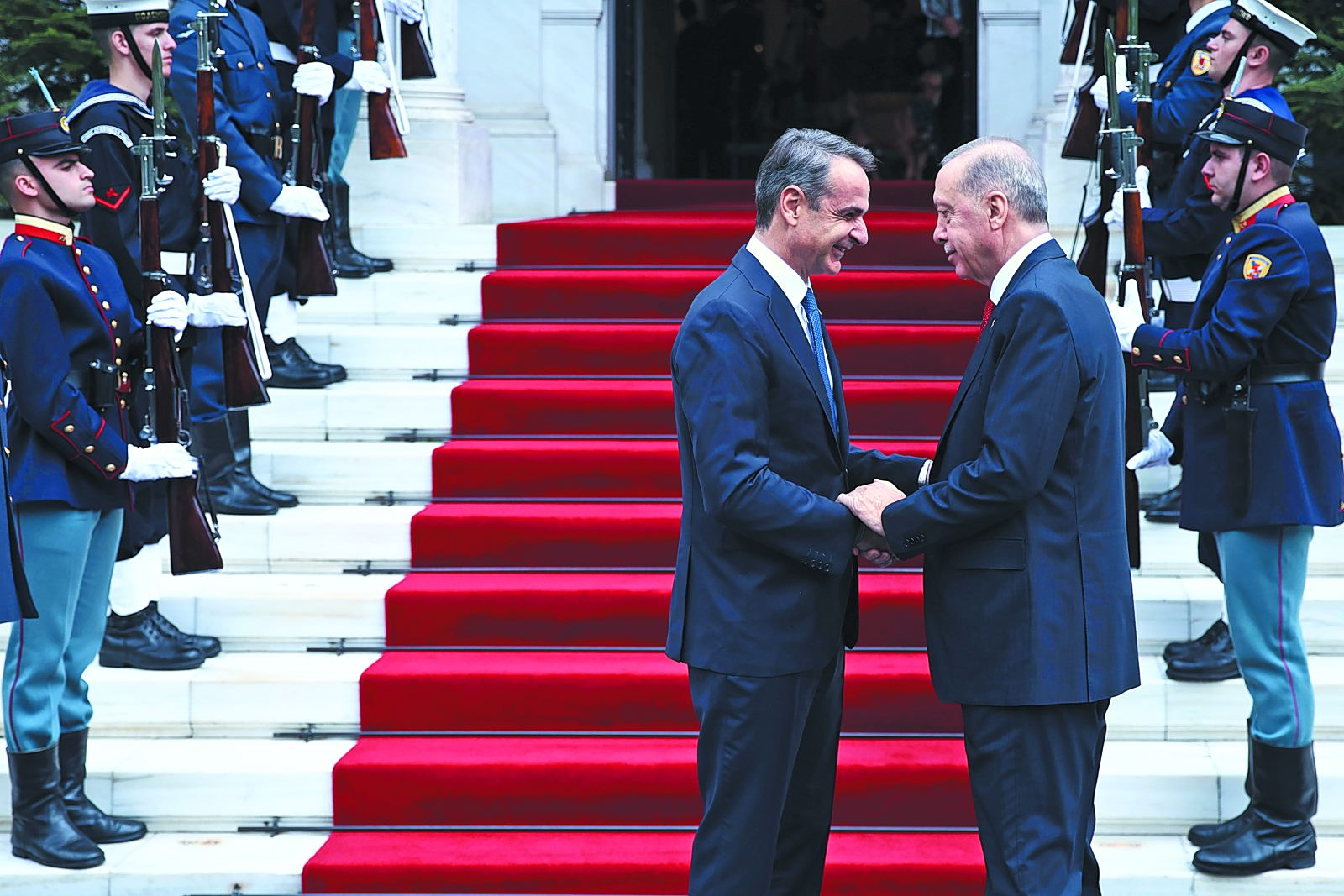

Recent years have seen Greek-Turkish relations run the gamut from the belligerent atmosphere of 2020 to the Athens Declaration of friendship in December 2023.

As we embark on 2026, there’s no doubt that relations have de-escalated, but equally so that they now find themselves at a crossroads.

Supposedly, Mitsotakis will be meeting Erdogan in the first quarter of the new year. The summit is to be held in Ankara, where the High-Level Cooperation Council between Greece and Turkey is finally set to meet after a delay. I hope it happens, because it, too, is part of the emerging sense of normalcy.

Until then, though, these are the facts we have to work with:

First, Turkey still wants what it wants, and its appetite is in no way diminished. Erdogan’s hardline New Year’s message must have brought a good many optimists down to earth with a bang.

Secondly, Turkey feels that it has grown in stature and will now be playing a more central role in the new international and regional environment. While its expectations may be a little outsized, they are grounded in reality.

Thirdly, the Greece of today is not the Greece of 2020. Economically stronger, Athens is proceeding with an expanded rearmament schedule and has consolidated its alliances in the Eastern Mediterranean.

So Turkey has not become a superpower, and Greece is no supplicant, either. Theoretically, they could find common ground for dialogue–even mutual understanding–if Turkey’s unfounded fears and vainglorious megalomania did not stand in the way.

At the same time, EU-Turkish relations remain essentially static. While European leaders are well aware how useful a Turkey could be for the EU’s Western inner circle, they also recognise that the prerequisites simply aren’t in place.

This explains the (real or inflated) reservations expressed by some when Cyprus took over the EU presidency for the first half of 2026.

What is certain is that relations with Turkey have never been easy or simple. Ankara is demanding a role no one is interested in conceding, and seeking to assert itself in a way no one appears willing to submit to.

Only if these ambitions are tempered can real scope for understanding be found. Provided, of course, that Erdogan can convince his Western counterparts he means what he says.