On the occasion of his first major solo exhibition at Roma Gallery, L’Infini terrible, Christos Oikonomou speaks to us about his relationship with the human body, distortion, trauma, and the paradoxical power of the smile in his work.

Christos Oikonomou

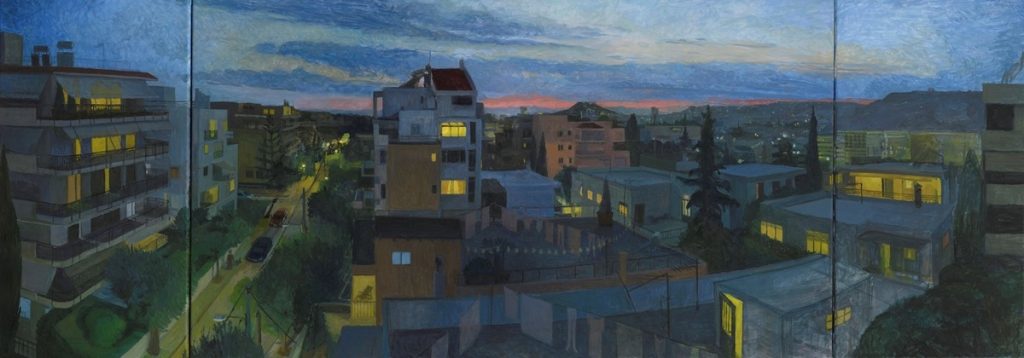

Born in Piraeus in 1998, Oikonomou has already established himself as one of the most distinctive voices of Greece’s under-30 artistic scene. Working primarily in ink and pastel on paper, his practice explores the human body as a field where psychic and physical tensions are inscribed. His works are dense with impulses, instincts, and distortions, carrying mythological, mystical, and real-world references, and embody a radical approach to trauma as lived experience—devoid of moral judgment.

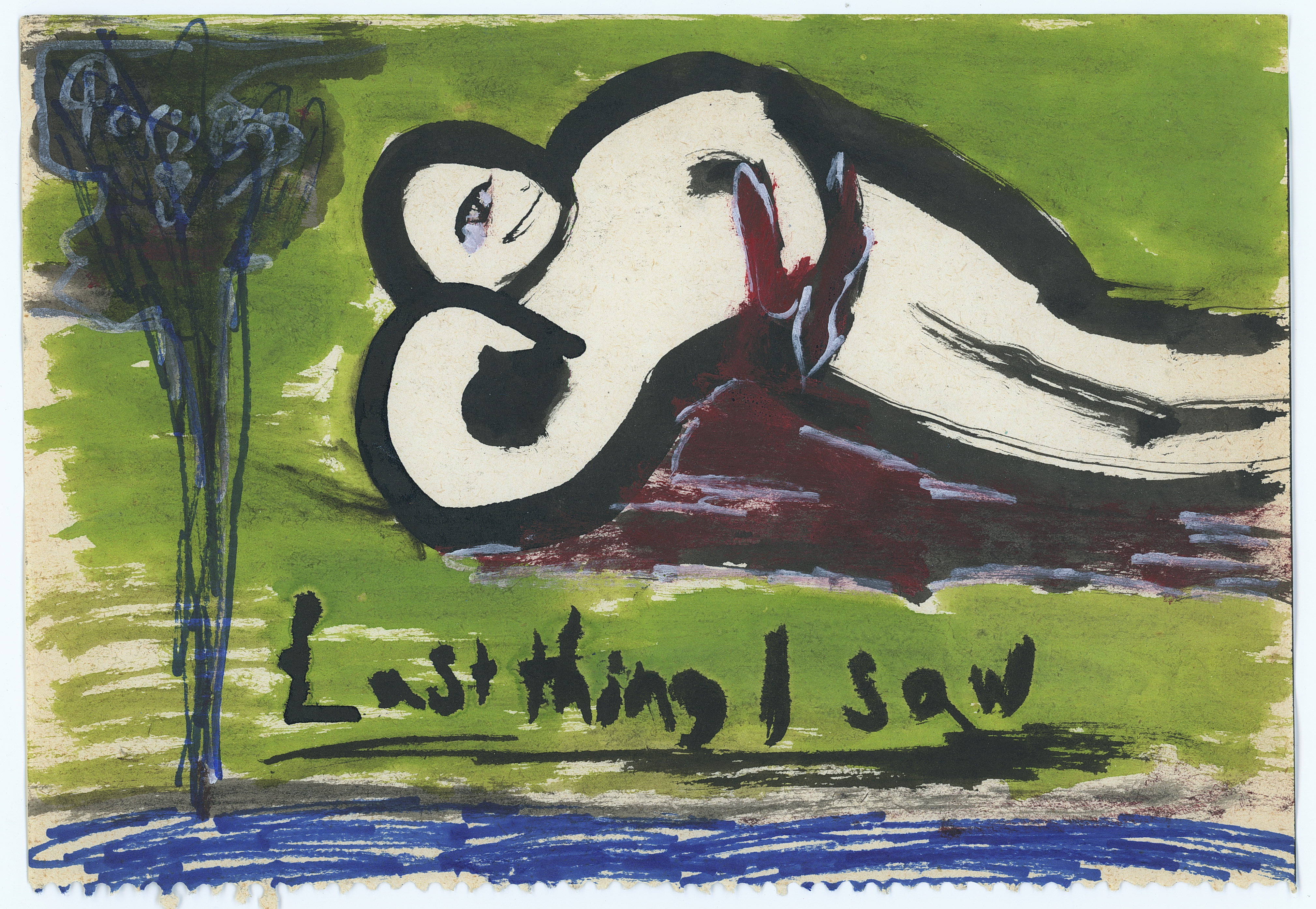

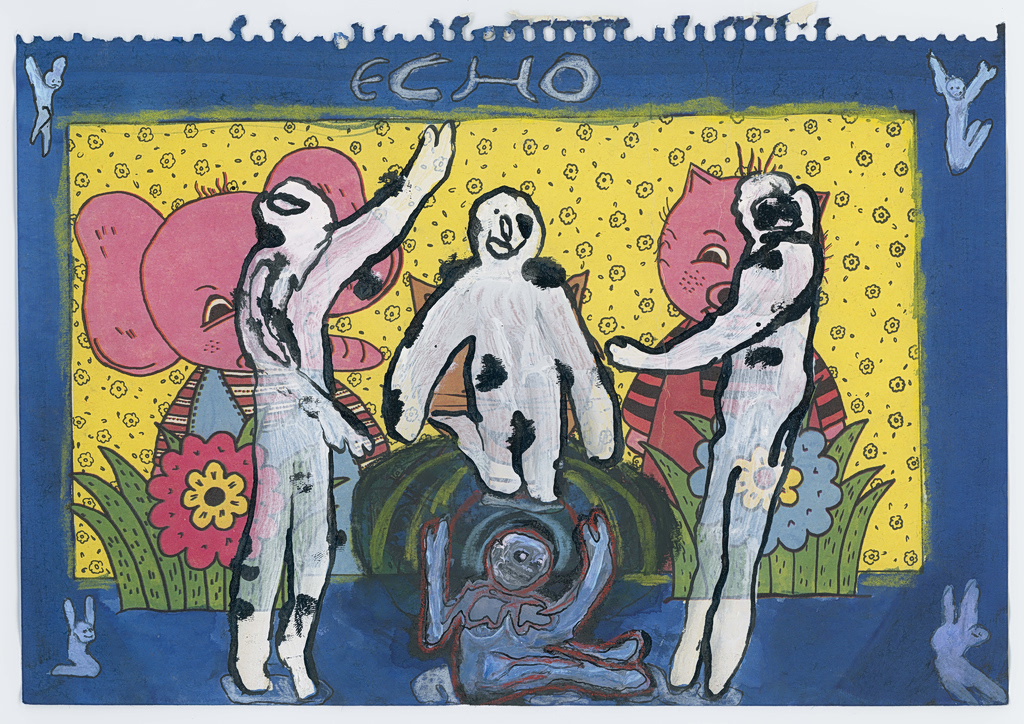

The exhibition brings together over sixty works created over the past five years, offering a representative survey of Oikonomou’s idiosyncratic exploration of the human form. Through the choreographed distortions and movements of his bodies, the works probe the tension between pain and pleasure, threat and grace, embodying the “terrible infinite” that shocks Ophelia’s blue eye in Rimbaud’s poem.

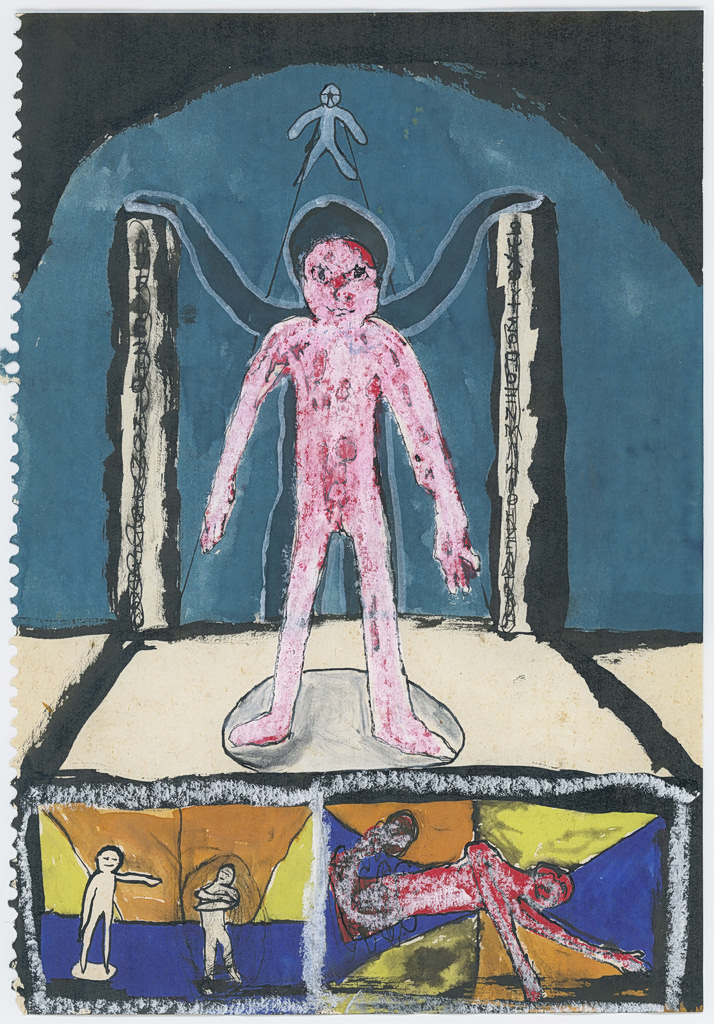

The Two Pillars, 2023, ink and pastel on paper, 24.5×16.5cm

Large-scale works such as Cuteness Aggression I & II, Close Encounters, and Return to the Source combine the playful simplicity of humanoid forms with an undercurrent of psychological intensity, while colors—cobalt blue, black, and carmine red—delineate liminal landscapes where corporeality hovers between childhood, tenderness, and menace.

In this context, Oikonomou speaks to us about how distortion, vulnerability, and trauma become fundamental conditions of human experience, and how the smiles of his figures act as a counterpoint to threat, revealing an extreme yet deeply truthful vision of the body and life.

The Birth of Self, 2022, ink on paper, 25.5x18cm

- Your first solo exhibition at Roma Gallery brings together more than 60 works produced over the past five years. How do you perceive your own evolution—and that of your practice—during this period?

The idea for my first solo exhibition at Roma Gallery emerged in the summer of 2025. It was followed by a series of studio visits and extended conversations around art, poetry, and everyday life, both in my studio and at the gallery, with the exhibition’s curator, Alia Tsangari, and the gallery’s owner, Anna Angelopoulou.

The selection of works developed organically, as the three of us observed the existing body of work and traced its dominant trajectories.

I recognise recurring lines of inquiry in my practice, centred on specific existential concerns, alongside a gradual evolution over time—technically, but also in terms of risk and experimentation. My early work developed in parallel with the formation of my thinking around vulnerability as a fundamental condition of existence. These works depict idealised bodies that, although subjected to violence, overcome the source of pain through the act of smiling.

In my more recent works, these smiles become firmer, more assertive. Fear appears to have been layered over—if not entirely absorbed.

Cuteness Aggression II, 2025, ink and pastel on paper, 40x30cm

- In L’Infini terrible, bodies are not so much represented as dissolved, distorted—almost on the verge of disappearance—yet they continue to smile. Is deformation a way of speaking about the body today? And what role does the smile play in your life and your work?

The way I construct images in my work resembles the structure of a sentence: subject, verb, object. For this reason, I am not interested in elaborate spatial settings. Space is usually reduced to a single line functioning as a horizon—much like a sentence unfolding along a line.

Bodies are the subjects. Their deformation results from the subject’s exposure to the external world. As in lived reality, the body remains perpetually vulnerable: time, a bullet, a bomb, or even another body can wound the vessel of the soul.

The figures in my work smile despite their injuries because I believe that once one transcends the materiality of the subject, there is nothing left to fear. The body has always been—and will always remain—the perishable manifestation of the experience we call life. Their smiles erupt as the inevitable consequence of recognising this truth.

Study of Cuteness Aggression, 2023, ink acrylic and gouache on paper, 40x30cm

- Let us remain with the body, which occupies a central position in your work. The distortions feel almost choreographic, as if the body were moving at the threshold between collapse and ecstasy. Yet your figures are often stripped of identity—gender, race, even facial features—while remaining profoundly human, almost religious. What purpose do identities serve today?

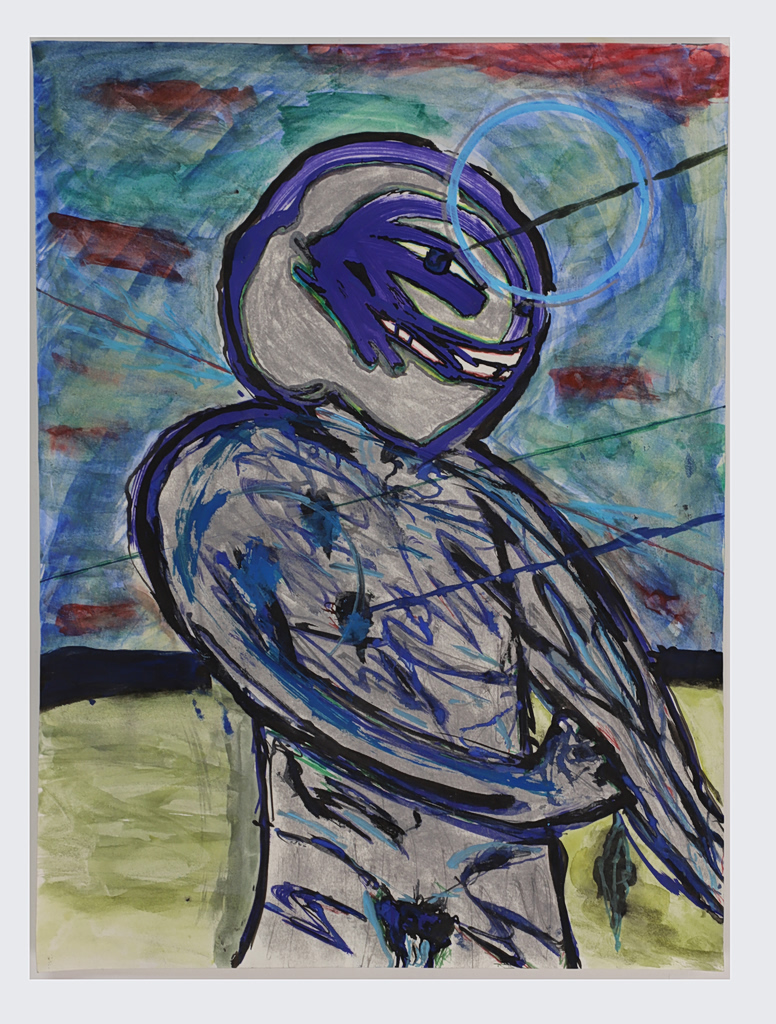

I deliberately depict bodies without clearly defined gendered or racial markers. This choice operates on multiple levels. Aesthetically, it references Cycladic figurines and, more broadly, the earliest representations of the human body. It is an attempt to approach a universal image of humanity, freed from spatial and temporal specificity—hence the use of nudity. If, for instance, the figures wore jeans, they would be immediately anchored to a particular era. In this sense, I approach the body archetypically.

I am also deeply influenced by Japanese anime, where one often encounters humanoid figures whose gender—or even whose humanity—remains ambiguous. By stripping away the markers of fixed identity, I want my figures to function as raw mirrors of human experience.

Defence, 2025, ink and pastel on paper , 24.5x16cm

- The “Terrible Infinite,” as you draw it from Rimbaud, Cavafy, and the Lacanian Real, appears impossible to approach without consequence. What price does the artist pay when moving toward this threshold, and what role does poetry play for you?

I have admired Rimbaud since childhood—for the courage, audacity, and jouissance with which he plunged into reality in all its forms. Drawing knowledge directly from the subjectivity of lived experience, he produced poetry of explosive intensity, capable of touching on universal concerns. He lived his life with pride, even amid decay.

What resonates most strongly with me is his complete acceptance of human tragicness, inseparable from joy. It is as though he possessed an initiated knowledge he never fully revealed—aware that beyond pain and pleasure lies a deeper, more radical form of liberation.

The price of confronting the terrible infinite is to lose oneself within it. Paradoxically, this seems to be the aim: the acceptance of the Ego’s continuous dissolution. Both Rimbaud and Cavafy offer, through their poetry, provisional maps for navigating the most demanding existential and aesthetic questions.

Halos of Pain 2025, ink and pastel on paper, 24.5×16.5cm

- You speak about trauma without assigning it moral value—neither as redemption nor accusation. In a world obsessed with “healing,” “catharsis,” or clear “messages,” why do you choose to leave trauma unresolved?

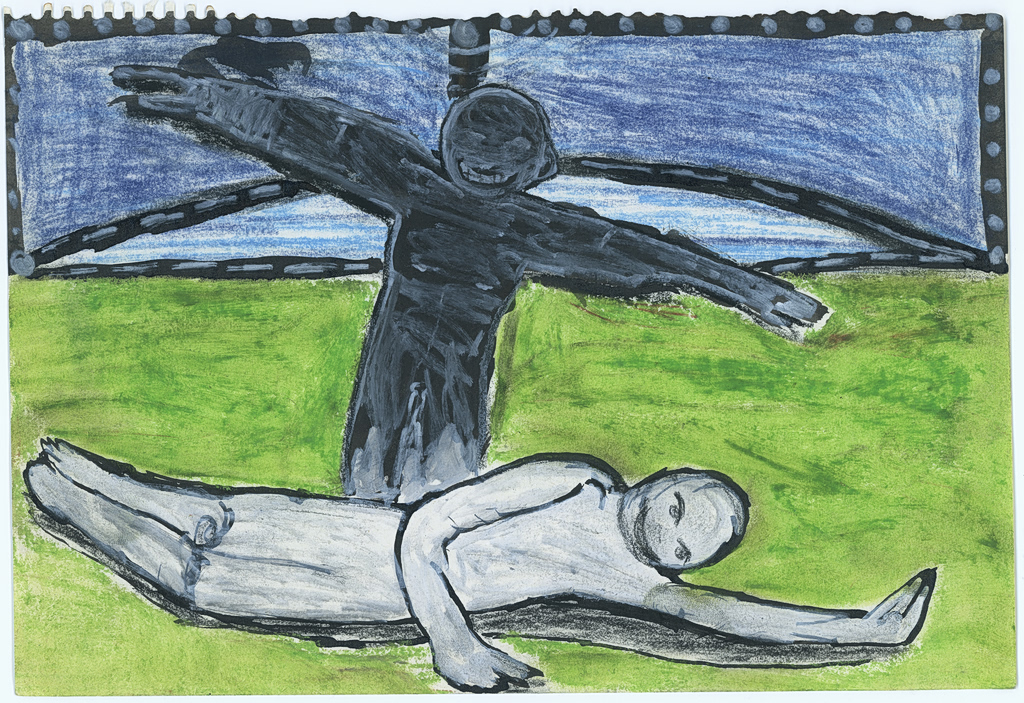

Trauma does not remain open indefinitely. I choose to acknowledge it and face it for what it is. Whatever occurs in one’s life—whether positive or negative—inevitably alters one’s original condition as a human being. To turn a rock into a sculpture, you must wound it. In essence, you are asked to transmute trauma.

My figures smile while wounded because they recognise vulnerability as the body’s permanent state. What lies beyond the body is what generates the smile. This is how trauma is “healed”: by being acknowledged as open and treated simply as the fact of a particular moment. Everything is transient.

Trauma does not define you, because you are the one who experiences it. Any search for redemption, I feel, is ultimately illusory.

Initiation, 2023, ink and pastel on trace paper, 24,5 x 16,5 cm

- You are only just over twenty-five, yet your work already engages with the extreme, the dark, the unrepresentable. Did you ever fear that by starting so “deep,” you might have nowhere left to go? And finally, what would you like viewers to take with them as they leave?

No. The infinite is inexhaustible, and this works in favour of anyone willing to face it directly. An idea can always be extended, revisited, transformed.

What matters most to me is that viewers are able to reconcile the smile and the wound in my figures—to recognise them as two sides of the same truth. By looking at trauma, one gains a clearer sense of how it may be approached.

I am not claiming that everything is pain. The bodies are wounded, and at the same time, they smile. Nothing more – and nothing less.

Last Thing I Saw, 2022, ink coloured pencil and acrylic on paper, 16.5×24.5cm